Writing

-

BACK TO THE FUTURE: Taize

I first visited Taizé in 1970. I was 16, and the Taizé community was just about to enter its heyday. The community had been founded during the Second World War, when a young Swiss, Roger Schutz, left the safety of his neutral homeland to live alongside the people of neighbouring France and share something of their suffering.

Taizé was near to the border of occupied and free France, and soon he was busy helping those pursued by the occupying German army to escape capture, and flee to Switzerland. Schutz was joined by a small group of friends, and so the tiny community began its common life.

By 1970, his story was being retold all over Europe, and increasing numbers of West European youngsters were coming to see for themselves this place of reconciliation, and share in its life. The numbers continued to grow. By the time of my second visit, in 1975, young people were coming in their tens of thousands; indeed, the numbers were so large that we sometimes spent the whole day — reading, talking, singing, discussing — in the meal queue.

Taizé had the optimism of the 1960s, and at times felt a little like a religious hippy commune. By day, we sat under the trees in discussion groups; each evening, we sang round a number of camp fires.

As a shy and rather anxious teenager, I found it confusing, and a little hard to engage. I was in a discussion group with eight other people; between us, we represented five denominations and four languages — an entirely new experience. But I was deeply touched by the worship, in the large concrete Church of Reconciliation, constructed in 1962.

It was not so much the spirituality as the participation of people of different traditions — they were saying the Lord’s Prayer next to me in French, Spanish, German, or Dutch — and discovering that I, too, could use their words to praise God in the multilingual chants of the Taizé liturgy. My eyes were opened to traditions, people, and languages beyond my own, and I began to understand the importance of ecumenism, as well as my responsibilities as a European citizen.

My last visit was in 1978, with fellow students from the Ecumenical Institute of the World Council of Churches at Bossey, near Geneva.

But this year, in the second week of Easter, I visited Taizé again — with Gerhard Tiel, a pastor in the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland, in Germany, who had also accompanied me on my last visit in 1978. The concrete church was still the same, but larger: it now had three waves of wooden extension at the west end. We still participated in discussion groups; mine included three French people, two Germans, and a lady from Hong Kong.

Taizé counted us as adults, not young people, and we had a special place to meet and eat, with just a little more comfort. We didn’t talk about denominations or our distinctive traditions — perhaps because the support of Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Churches, is now accepted, understood, and embedded. At any rate, it didn’t seem to matter: we talked from our shared Christian and “adult” experience.

Beyond the 60 or so adults, there were about 2000 young people — many of them German — whose energy and exuberance brought Taizé alive, as it had done 40 years before. The numbers were smaller than I remembered, and there were fewer from the UK, but the languages were more extensive, and now included Polish, Bulgarian, Swahili, and Chinese, reflecting a wider Europe, greater mobility, and our engagement with a bigger world.

It was challenging in a number of sometimes contradictory ways. The perspective was wider, the different traditions less important, the variety greater, the numbers smaller.

But it is time to come down from the mountain, and I have returned home to Brexit, tensions with Russia, cybercrime, the NHS funding crisis, and more knife attacks on the streets of London . . . and, in the Church, declining numbers, a shrinking church voice in our national life, church leaders who are tired and stressed, and finances on a shoestring.

I wonder how far, as a Christian community, we can continue to afford the luxury of division, divergence, or mutual suspicion, as we struggle to maintain separate buildings and church infrastructures in parallel. Taizé has nudged me to find a renewed enthusiasm for ecumenism; an energy to try again to address and overcome those challenges that so constrained the previous generation of ecumenists, and lost us the past 40 years. As Brother Roger so simply put it, “Make the unity of the body of Christ your passionate concern.”

©Hilary Oakley

Image Evening Prayers in the Church of Reconciliation, Taizé, Wikimedia Commons

This article first appeared in The Church Times, 27 July 2018. -

Holy Saturday

We find ourselves with Mary, the mother of Jesus and the others who loved him, in a place of many overwhelmings this day.

The death of love, the brokenness of life, fear of the unknown, the fading of beauty, paradise lost, the going down into hell.

So many words to describe that word, hell. Underworld, Sheol, Hades, Gehenna, Abraham’s bosom. A place where we come face to face with our deepest dark, our fragility, our captivity to diminishment. A place of abandonment, no fragment of light.

Was Jesus’ death a dread defeat, a victory for demonic forces, a chilling vindication of those who destroy Christ, then or now? Not delivering on his promise to provide a new ordering of life, restoration, forgiveness?

On this day between crucifixion and resurrection, Jesus harrowed out of hell all the dead held captive there since the creation of the world. He took them by the hand and led them to Life.

‘When the gatekeepers of hell saw him, they fled; the bronze gates were broken open, and the iron chains were undone.’[i]

On this Holy Saturday, may we remember the ones

…who know their need, for theirs is the grace of heaven.

…who weep, for their tears will be wiped away.

…who are humble, for they are close to the sacred earth.

…who hunger for earth’s oneness, for they will be satisfied.

…who are forgiving, for they are free.

…who are clear in heart, for they see the Living Presence.

…who are the peacemakers, for they are born of God.[ii]And so we wait for the Third Day

in stillness

with a fragment of light

trusting and hoping…©Hilary Oxford Smith

Image Candle Light, Hans Vivek, Unsplash.com -

A Shadowed Path

Dawn on the Otago Peninsula. We awoke to the clarion call of a cockerel, heralding the blessing of a golden Autumn day. Jonathan Livingston Seagull shared wisdom in the sky. White feathered kotuku-ngutupapa or Royal Spoonbills, swept the low tide line of the harbour for breakfast. In the court of heaven on earth, four Royal Albatross or toroa, glided through the air, with what Herman Melville in Moby Dick, described as vast archangel wings.

William Wales, a tutor to the English poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the astronomer on HMS Resolution, voyaged with Captain James Cook to the land of ice, the southernmost continent we now call, Antarctica. Inspired by hearing stories of the sea and a fabled land, Coleridge wrote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, an epic tale about an albatross and the sailor who kills it with a crossbow.

The poem is replete with imagery, allegory, superstition, and allusion. The punishment for what the sailor has done is to wear the dead bird around his neck and the rest of his life becomes one of penance as he wanders the earth, telling his salutary tale. He learns wisdom along the way, that God's creation is a beautiful gift, to be cherished.

On Palm Sunday, we attended Choral Eucharist in St. Paul's Cathedral, Dunedin and sang, Ride on! Ride on in majesty! Sacrificial theology excepting, one line stood out for me,

Ride on! Ride on in majesty!

The wingèd squadrons of the sky look down with sad and wondering eyes to see the approaching sacrifice.I imagined that an albatross with vast archangel wings might be amongst the sorrowing company of heaven.

In the mystery of this week we call Holy, with its darkening shadows of pain and fear, abandonment, uncertainty, betrayal, and death, might we somehow contemplate in the stories, something of the novelist, Jeanette Winterson's words, the nearness of the wound to the gift?[i]

- Mary gently caressing the feet of Jesus with her long hair and extravagantly scented perfume, preparing him for what lies ahead.

- Jesus, with intimacy, humility, and oneness, washing the dust from the feet of his disciples.

- The mystery of the memory and substance of Jesus’ presence, as he and his friends share food and wine.

- John, the disciple, whom Jesus especially loved, placing his head on Jesus’ breast in closeness, affection and love, hearing the heartbeat of God.

- Veronica, tenderly wiping the blood and sweat from Jesus' face with her veil, his likeness forever imprinted on her heart.

- Simon of Cyrene, forced to carry the cross through the narrow streets of Jerusalem when Jesus could no longer bear the weight of it. His life changed forever.

- Jesus' mother Mary, the other faithful women, and John, accompanying Jesus every step of the way, hearing his loving words of familial care and loyalty.

- In his dying moments, self-giving love and grace shared with a thief, crucified beside him.Then the night of deepest loneliness. A total absence of his spirit and his life.

At dawn, wounds become places where the light enters us. Grace takes us to the cherishing of life and the nurturing of love. The images and the echo of words we thought we had lost or left behind create a sanctuary of memory in our hearts.

His eyes sparkle again. He tells stories by the sea. He blesses us with Love.

©Hilary Oxford Smith

Image Around the Shag Rocks, Light-mantled Sooty Albatrosses, Keith Shackleton, 1979. Nature in Art, Gloucester, UK.[i] Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, Jeannette Winterson, 230pp, Grove Press.

-

The Temple in His Bones

Reading from the Gospels

Lent 3, Year B: John 2: 13 – 22On my first afternoon in Rome a few years ago, I climbed on the back of my friend Eric’s motorcycle and set off with him to begin my acquaintance with the Eternal City. A few minutes down the road, he told me to close my eyes. When we came to a stop and I opened them, my field of vision was filled with one of the most impressive sights in a city of impressive sights: the Pantheon. Built in the second century AD, the Pantheon replaced the original Pantheon that Marcus Agrippa constructed fewer than three decades before the birth of Christ. A temple dedicated to “all the gods” (hence its name), the Pantheon became a church in the seventh century when Pope Boniface IV consecrated it as the Church of Santa Maria ad Martyres. It’s said that at the moment of the consecration, all the spirits inhabiting the former temple escaped through the oculus—the hole in the Pantheon’s remarkable dome that leaves it perpetually open to the heavens.

As churches go, it’s hard to top the Pantheon for its physical beauty and power. It was perhaps risky to see it on my first day, so high did it set the bar for the rest of my trip. Yet Rome, of course, brims with delights for the eyes, and the next two weeks offered plenty of stunning visual fare. Amid the calculated grandeur, I found that it was the details that charmed me: the intricate pattern of a Cosmatesque marble floor, the shimmer of light on a centuries-old mosaic, the inscribed marble fragments that had been unearthed and plastered to the walls. It was staggering to contemplate the countless hours and years that went into the construction of these spaces, or to fathom the vast wells of talent and skill that generations of architects, artisans, and laborers lavished upon them.

The Roman churches that most linger in my memory are those that possessed a clear congruence between the physical environment and its purpose—those places of worship that were not primarily tourist destinations but true sanctuaries. I felt this congruence keenly, for instance, in the Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere. The space intrigued me from my first moments in it, on the first evening of my trip. I would return several times, learning along the way that one of the many ways the church serves the surrounding Trastevere neighborhood is as a place of prayer for the Community of Sant’Egidio, a lay movement of people who work for reconciliation, peace, solidarity with the poor, and hospitality to pilgrims.

On the day that Jesus sweeps into the temple, it’s this kind of congruence that is pressing on his mind. We don’t know precisely what has him so riled up; after all, particularly with Passover drawing near, there are transactions that need to take place in the temple. As Jesus enters, he sees those who are attending to the business involved in the necessary ritual sacrifices, but he seems to feel it has become simply that: a business. Commercial transaction has overtaken divine interaction. Time for a clearing out, a return to congruence between form and function, to the integrity of the purpose for which the temple was created: to serve as a place of meeting between God and God’s people.

To those who challenge his turning over of the temple, Jesus makes a remarkable claim: that he himself is the temple. “Destroy this temple,” he says to them, “and in three days I will raise it up.” His claim stuns his listeners, who know that the sacred space in which they are standing—the Second Temple, which was in the midst of a massive renovation and expansion started by Herod the Great—has been under construction for forty-six years. John clues us in on the secret that the disciples will later recall: “He was speaking of the temple of his body.”

This scene underscores a particular concern that John carries throughout his gospel: to present Jesus as one who takes into himself, into his own body and being, the purpose of the temple. Richard B. Hays writes that in making the link between Jesus’ body and the temple, this passage provides “a key for much that follows” in John’s gospel. “Jesus now takes over the Temple’s function,” Hays observes, “as a place of mediation between God and human beings.” Hays goes on to point out how Jesus’ sometimes enigmatic sayings about himself in John’s gospel—for instance, “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me, and let the one who believes in me drink” and “I am the light of the world”—are references to religious festivals whose symbolism Jesus takes into himself.

Perhaps, then, it all comes down to architecture. The decades of work that have gone into the physical place of worship, the skill of the artisans, the labors of the workers; the role of the temple as a locus of sacrifice, of celebration, of identity as a community; the power and beauty of the holy place: Jesus says, I am this. Jesus carries the temple in his bones. Within the space of his own body that will die, that will rise, that he will offer to us, a living liturgy unfolds.

We will yet see the ways that Jesus uses his body to evoke and provoke, how he will offer his body with all its significations and possibilities as a habitation, a place of meeting, a site of worship. Calling his disciples, at the Last Supper, to abide in him; opening his body on the cross; re-forming his flesh in the resurrection; offering his wounds to Thomas like a portal, a passageway: Jesus presents a body that is radically physical yet also wildly multivalent in its meanings.

The wonder and the mystery of this gospel lection, and of Jesus’ life, lie not only in how he gives his body as a sacred space but also in how he calls us to be his body in this world. Christ’s deep desire, so evident on that day in the temple, is that we pursue the congruence he embodied in himself: that as his body, as his living temple in the world, we take on the forms that will most clearly welcome and mediate his presence. In our bodies, in our lives, in our communities; by our hospitality, by our witness, by our life of prayer: Christ calls us to be a place of meeting between God and God’s people, a living sanctuary for the healing of the world.

The season of Lent beckons us to consider, are there things we need to clear out in order to have the congruence to which Christ invites us? Who helps you recognize what you need to let go of in order to be more present to the God who seeks a sanctuary in you? How is it with your body—your own flesh in which Christ dwells, and the community with which you seek to be the body of Christ in the world? What kind of community do you long for—do you have that? What would it take to find or create it?

In these Lenten days, may we be a place of hospitality to all that is holy. Blessings.

©Jan Richardson

©Image The Temple in His Bones, Jan Richardson[Richard B. Hays quote from his chapter “The canonical matrix of the gospels” in The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels, ed. Stephen C. Barton.]

-

Implications

a divorce

a stoning

a broken betrothalshame

rejection

family life fracturedscandal

division

broken hearts and troubled mindsall these and more

the possible implications

in the wake of Mary’s ‘yes’is this what

favour with God

looks likecould we too

say the Mighty One has done great thingswould we

be able to magnify the Lordhow will we respond

when our calling comes,

in the face

of myriad implicationsMary

unreservedly

willingly

quietly consented

to birth the One

who would later say

take up your cross

and follow mecan we respond with such incredible grace

©Pat Marsh

Image artist unknown

-

We See The Light

In violent times,

beautiful words,

centuries old,

resonant with truth:‘Because of your light, Lord,

we see the light.’*That light, even now,

illumining

our terror-stricken age

with the possiblity of change:

offering our over-burdened hearts

a resting place

that a deeper compassion

may be our companion –an energy of love

to struggle for justice,

to be a wounded healer,

to share what we have,

to carry hope in our hearts,

to laugh and to love,

perhaps, all in one day!©Peter Millar (previously published in Candles and Conifers, Wild Goose Publications)

Image Holding in the Light, www.cofchrist.org.

-

Called from our Desert Places

(Advent 2b: Isaiah 40:1-11, Mark 1:1-8)

I am sure that each of us has at some point tossed a stone into a lake and seen ripple after ripple come from the epicentre, the place where the stone hits the water. One little thing seems to have an impact out of all relation to its actual size. The German philosopher Johann Fichte, and I swear this is as high brow as I’m going to get, wrote this about the impact of a seemingly insignificant act:

you could not remove a single grain of sand from its place without thereby changing something in all parts throughout the immeasurable whole.

Though he could not know it, he was one of the intellectual founders of what we now know as the butterfly effect; a belief that apparently small insignificant things – like the flapping of a butterfly’s wings – can have a major impact on the world.

We live in a cycle of cause and effect, we begin things that we cannot know where they will l lead to, we act in certain ways because events far away and possibly long ago have determined that this is how we will act.

One hundred years ago British and ANZAC forces captured Palestine. The British seeking to gain the loyalty or at least the acquiescence of the population made different promises to the Arab and Jewish communities. The former were promised national self determination, the latter – in the Balfour Declaration – were promised a ”national home.” Of course, the British took over the running of Palestine so there was no self determination for the Arabs and in time the Jewish community in Palestine became a Jewish State; the same UN vote which permitted a State of Israel also authorised a Palestinian state but the Arab states determined this could not come to be until Israel was destroyed.

Even following a partial Arab recognition of Israel, the conditions for a Palestinian state have been elusive. Words the British used to placate two different populations never went away, words said to buy cooperation and keep the peace have fed conflict and war.

While Britain became the protecting power in Palestine, New Zealand took over responsibility for what had been German Samoa. Another little flutter of butterfly wings which has been felt over time, changing history for both the people of Samoa and the people of New Zealand. Our stories have become intertwined in ways that could never have been imagined way back then.

Strange isn’t it? That the farthest ripple of a war which began with an assassination in the Balkans was a change in who governed some far away islands deep in the South Pacific; a real butterfly effect. But World War One changed so much and not with the delicate flutter of wings. In the words of W.B. Yeats whose The Second Coming we heard last week, all was changed and changed utterly.

Small, seemingly insignificant things ripple still. Nowhere more so than in our impact on the environment. Think of how many plastic bags you have used in the last year, where do they end up, or the plastic microbeads in shampoos, conditioners, shower gel; where do they go? Ultimately it seems much of it goes down to the sea where it does great harm. The world itself is in pain and in need, and so too are we. We are not – like Yeats – emerging into a world that has changed and changed utterly – but for much of humanity, life is more fragile, stability more precarious, peace more elusive than here.

The world itself needs newness, so do people everywhere; it has always been this way.

The truth of it is that it was ever thus. Since the beginning of time, it seems that thoughtful people have taken a good long look at the world around them and, with a shudder, have decided they don’t like what they see. It was certainly true of Jesus’ time and place.

The time and place Jesus was born into and which was seen as the context of his ministry was marked by occupation, oppression, injustice and brute force. It was a broken place, like every place there has ever been maybe! And in Advent we are invited to reflect on and name that brokenness which stands in need of redemption.

The German theologian and martyr – Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote

the celebration of Advent is only possible to those who are troubled in soul, who know themselves to be poor and imperfect, who look forward to something greater to come. For these, it is enough to wait in humble fear until the Holy One comes down to us. God in the child, in the manger.

Both our readings today are food to the soul that waits. The promise of a new day dawning.

If you look at classical art based on the Advent stories, say of Gabriel’s annunciation to Mary, it is often set in a world which seems faded, broken down, littered with the ruins of the past. There is something of Bonhoeffer’s point in this. Advent speaks to our turmoil, our failure and brokenness and offers hope where hope seems to have fled.

A colleague when I worked in Mental Healthcare once said of the world that if you’re not depressed, you’re not paying attention. His point was that being depressed is an entirely rational response to how the world is and we kind of get his point.

Advent isn’t about saying the world is just fine, or that we live in the best of all possible worlds; what it’s saying is that another world is possible, that there is a better way despite the darkness, the sorrow and brokenness which mar and wound the world.

Our reading from Isaiah speaks to this. It comes at the beginning of what biblical commentators call Deutero Isaiah, the second part of the book. The first part – what went before – was dominated by loss, exile, the threat of the disappearance of the Covenant people from history. This second part is concerned with the end of exile and the possibility of a new beginning.

Our reading began with these words, Comfort, o comfort my people. Well known words. If I were a half decent tenor I might attempt a spot of Handel at this stage! But I’ll spare you that, I can carry a tune but not far.

What follows speaks of the possibility of newness. The part of the text most familiar to us Christians, especially at Advent, is:

In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

Words echoed in the beginning of Mark’s Gospel, words which Christians immediately associate with John the Baptist, whose story we read as being an anticipation of and preparation for the story of Jesus.

John is presented to us as calling for repentance and the forgiveness of sins, rather forbidding language, language we do not use much in this church. Repentance can have a bad name, it can carry overtones of preoccupation with sin and those who preach it can appear to be manipulative.

But what it means, simply and undramatically is to change, to change your bearings, to go in a new direction. Repentance was an act of hope in the possibility of the new and an acknowledgement that for the new to come to be, then people had to live differently.

Though he is an odd character, angular and uncomfortable, living there on the edge of the desert in animal skins, surviving on honey and locusts, John is a charismatic personality, he draws a crowd. People are drawn to him and to his offer of newness and they present themselves for ritual purification, total immersion in moving, flowing water; the Jewish ritual origin of our baptism. It wasn’t magic, it didn’t change the world, but it was a cleansing, a statement of intent to live differently.

This is all very interesting – I hope – but what can it say to us, these stories from far away and long ago? That they speak in our wilderness now, in our experiences of exile, of alienation, or sense of a fractured and wounded world, of our need for newness.

We too are called, invited to turn in a new direction and to live differently, to live in the direction of wholeness, to live in the direction of justice, to live in the direction of mercy, to live in the direction of the world’s healing.

In these remaining Advent days, as the days lengthen may we know that other brightness, the light of holy possibility, the light of newness, may it shine brightly and lead us once more to our every Bethlehem.

©The Ref. David Poultney

Image Preparing a Way in the Wilderness, Hermano LeonDavid is Prestyer of St. John’s in the City Methodist Church, Nelson, New Zealand

-

Two Halves of the Moon

Like a Slope Point tree in Southland, a tree, windblown on the Arctic side, tinged with sea-salty rust, retreats ever inwards in the wild and briary glebe of the clergy house. It is the calm before another winter storm on this side of the world. Little penguin-like auks have been blown off course by the tempest of last week and are now regaining their energy in Noah’s Ark – the local animal rehoming centre. Rivers burst their banks, the turbulent waters ravaged homes, leaving silt and rainbow trout in their wake.

An Epiphany sun shone for an hour or so today. And my eye was drawn to wandering dolphins and orcas in the Firth and a weather-beaten fisherman hauling lobster creels onto his rusty fishing boat. There aren’t many lobsters about at the moment. The gourmands, dining in London restaurants, will have to do with monkfish.

Meanwhile, the people of the besieged Syrian town of Madaya, weep, as food finally reaches them. Starvation is used as a weapon of war in a conflict that grows more desperate with every moment. Prayers beam eastwards.

After Christmas, clergy need to drift away from the collage of parish life. I washed up on the Ardnamurchan Peninsula, a remote and wild place in the Western Highlands of Scotland. The landscape tells a harsh, sometimes violent, often sad story…of volcano fires, blood-soaked battles, the religious fervour of Irish monks, rampaging Viking invaders and Highland Clearances.

Like Alice Through the Looking Glass, it was as if I had entered a wormhole, travelling through a mirrored world of scarred mountain rifts, moine rocks, fossils and rainfall, to the vanished world of Central Otago.

Tramping in the Sunart rainforest, green with lichens, mosses and liverworts growing from bark and branch, I came across a clearing and a timber house, called Kaikoura - MÄori for ‘meal of crayfish’.

At land’s end, the most westerly point on the peninsula, stood the only Egyptian-style lighthouse in the world, with figurines of pharaohs, gods and sphinxes decorating the lamp base. In the fading light of a winter’s day, the Atlantic Ocean hurled itself at the beacon, biting pieces off the rocks.

I watched an unfolding ferocity that only the gods could have summoned. It was a night when the light would be needed most and I imagined that it beamed across the waters to Dusky Sound.

Back home in the village, the people celebrated the beginning of a three hundred year anniversary. In a New Year and in a bare hall, sheltered from the January cold, we looked back and, as I prayed for God’s blessing, we looked forward, to the unknown.

The schoolchildren sang songs about silver darlings, the Scottish name for herrings. If Alice had been there, she would have danced a lobster quadrille with seals, turtles and salmon.

Meanwhile, the air is sweet in a nativity summer. Kayakers paddle down the Clutha River and barbecues smoke on the beach. Yachts anchor in Half Moon bay as night falls, while children watch their shadows and play in the light of Curious Cove.

Two halves of the moon.

©Hilary Oxford Smith

Image Two halves make one moon? Flickr., Creative Commons 2.0 -

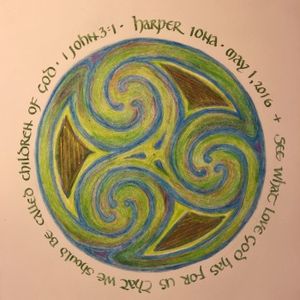

Come Unto Me

Which comes first? Baptism or Communion? Baptism is not a requirement for communion and so I have heard the new PC(USA) Directory for Worship hopes to affirm the free and abundant grace of God we find at the Lord’s table. No exceptions. I have, for some time, embraced an open table and I believe the Church, not only the Presbyterian Church (USA) is opening to the idea of sacrament as welcome and inclusion. I confess that I enjoy worshipping at an Episcopal Church where this unconditional welcome is crystal clear.

Earlier this year I was asked to celebrate an “extraordinary” baptism. Of course, all baptisms are extraordinary, but this would be a baptism that bends the rules, stepping just outside the doors of the church. Sara Miles, in Take this Bread, had already suggested to me the idea of a font outside the doors of the church.

My nephew and his bride grew up in the church, Presbyterian and Lutheran respectively. Like most of us, there have been times when they felt excluded and alienated by the church. They are now young parents, both working hard to balance family, work, and pleasure. They were married by a beloved pastor in the great outdoors, with the mountains as a backdrop. When they began to think about baptism for their daughter, Harper Iona, the doors were closed to them unless they became members of the church. And the font was behind those doors.

They say that young adults don’t think about membership the way we boomers and older folks do. I thought about all the ways the old-line, mainline churches are trying and failing to welcome younger adults. I thought about all the baptisms I had celebrated inside the church, where the parents made their promises out loud, but were never seen again on a Sunday in church. I also thought about the Church of Scotland where I have served, and the way that they have wrestled with this very question, loosening up a bit on the membership requirement.

When asked to baptize Harper, I so very much wanted to say “yes.” My initial response was, I so want to do this, but we would need to figure out a way to make it an “official” baptism. It would not be a blessing or a dedication. It would not be a private baptism. I was willing to bend the rules, but I have become increasingly sacramental over the years. When I asked the parents why they wanted Harper baptized, they had all the right answers. She is a child of God. We want to say that out loud to our family and friends. And, yes, we will profess our faith out loud. And, yes, we will promise to raise her in the church. And, yes, everyone there can gently remind us that we need to find a church. And we will. In time.

So I read and reread the Directory for Worship. And the Bible. And I talked to a few clergy friends in various traditions. And I even talked to a couple of polity wonks to try to figure out a way to do this.

And then I attended another baptism inside the church and realized that very few Sunday morning baptisms follow the Directory for Worship to the letter. They happen before, not after the sermon. There are no renunciations. Hardly ever is the Apostles’ Creed recited by one and all. There may or may not be an elder present. Questions may or may not be asked of the congregation. Session may or may not have recorded it in the Register.

Over the years, teaching Reformed Worship, when “extraordinary” cases in point were raised in class, I always told my students to wrestle with three things: the pastoral, the theological, and the ecclesial. And of course, the Bible. The ecclesial requirement of membership in this case seemed a way of pushing this young family further from the church. I prayed. I conversed. I listened. I read. I wrote. And I decided that I could create a sacramental service of worship that honored the Directory for Worship, but more than that, honored the spiritual lives of this family, Reformed theology, and the Word of God.

Gospel words began to ring in my ears: “Suffer the little children to come unto me and forbid them not, for to such as these belongs the kingdom of heaven.” “Wherever two or three are gathered in my name, there I am in the midst of them.” “God is love, and those who love are born of God and know God.” “Here is some water, what is to prevent me from being baptized?”

So I said, “yes.” And I conducted a service of worship outside the doors of the church, but with a gathered community of family and friends who would sing and pray, who would hear the Word proclaimed, who would respond by professing their faith, and by witnessing the promises of these young parents. Both great grandmothers are elders, so they stood with me as those gathered promised to support this family. Two close friends were sponsors. The only missing piece, in this case, was that the baptism would not be recorded in any congregation’s minute book. I made them a very beautiful certificate and signed it!

It was an extraordinary event for so many reasons. But in the thinking and the praying and the planning and the celebrating, I was changed. A sacrament is a visible sign of an invisible grace. That I have long believed. But a sacrament ought not be a way of excluding anyone from that invisible grace. A sacrament ought to be an invitation, a welcome, a reaching out, evangelism. We can no longer wait inside the church, behind closed doors, waiting for young families with children to push their way in.

I am honorably retired, so not as worried as I might have been a few years ago about breaking or bending the rules. I know that I am way more “by the book” than so many younger, edgier pastors who would say, “What’s the big deal?” By narrating this event, I am refusing to fly under the radar. I am professing a scruple. At least. So defrock me.

We are sacramental. I am a Minister of Word and Sacrament. A priest. We are to tear down the fences and the dividing walls. The doors of the church ought to be open. Always. So, if I believe in an open table, where all are welcome, baptized or not, then I believe in a font that is right there, right near the open doors of the church as a sign of welcome. As a visible sign of invisible, lavish grace. And filled to the brim. Always.

©Rebecca Button Prichard

Image Baptism Certificate made and gifted to Harper Iona and her parents from Rebecca.

www.rebeccaprichard.com

-

Between the Tides

I barely got on the plane. My stomach reflux flared up again after a workshop in Manchester. My doctor in Sydney had given me enough tablets to tide me over until I started my sabbatical in New Zealand, a three-month fellowship at a retreat centre on a sheltered strip of beach at Long Bay. But not even strong medication could quell my familiar companion as I took leave of absence from work and any semblance of home.

My body must have known it was headed in the right direction as soon as we lifted above the clouds. We crossed over Erbil where refugees sought safety in the Kurdish capital thousands of metres below my window seat and continents away from the safe haven awaiting me. I had never felt more grateful to be on a plane.

‘The project you came with may not be the project you leave with,’ warned John Fairbrother, the director, over our first cup of tea in the dining room.

I’d applied to write stories of displacement, the lost threads of girls who’d fled war. Bright roses, cats and birds, someone’s initials, the intricate patterns and colours of homes and families embroidered onto cloth that a museum in Vienna had boxed in darkness for a century. To mark the war’s centenary the museum exhibited the refugees’ handiwork. I gave my first public lecture in Vienna two days before the workshop in Manchester.

Two years later it all seems like another lifetime. John was right. I left my project and profession and discovered my own silent threads in the dark.

Before I arrived at Vaughan Park, I’d struggled to articulate the displacement in my chosen academic life. As though my language of the past had been buried by a wave crashing from a Pacific storm and spreading its white foam carpet over my ground of understanding. As the storm receded and left a beach full of broken shells, I started to learn to live between the tides, carried by the ocean’s breath.

‘It’s like being inside Mary’s womb,’ a visiting Episcopalian priest described the retreat centre chapel that overlooked the water.

We were speaking after mass on the feast of Mary’s assumption six weeks into my sabbatical, but her words had nothing to do with a liturgical event. Suddenly I saw what had been happening to me in the rhythmic swelling and falling, crouching on slippery rocks and climbing steep cliffs, sitting on the heated tiles of the chapel floor with the day disappearing behind green hills. Hearing the older woman’s voice outside the chapel I knew it was time. I wrote my first words of resignation as inexplicable as the assumption.

Six weeks of pacing cliffs and rocks came to a standstill. Once the inward process of leaving was set in motion I kept close to the centre, only venturing out for an errand or to sit in a café in the rain. At night I took my thermos of tea to the top of the retreat centre to watch the moon from a miniature shell garden in the shape of a koru unfurling.

Sometimes it takes darkness, poet David Whyte says, to learn / anything or anyone / that does not bring you alive / is too small for you.

In the presence of the moon I asked what might make me alive, doubted about ever outgrowing the confines of these broken shells, wondered if I’d be able to learn not just when to leave but also when to stay. I’d been moving so long, I didn’t know how to stop. The moon had travelled even longer than me, but she seemed to understand my need for stability. I’d stopped believing in an itinerant God who travelled to earth and died homeless. If she was a mother, she’d know how to make a home.

The stories that touched me most at Vaughan Park were the mothers of high needs children who came to unburden and find strength to give again. I could see the difference in their faces from Friday evening to Saturday as they opened up at dinner after a day of massages. The quilters were some of my favourite retreat companions with stories as vibrant as their recycled fabric: Japanese kimonos worn by monks stitched into a wedding present for a bed, scraps sewn into a keepsake for a friend or grandchild. The loudest group turned up on their motorbikes for a white ribbon ride around the country. Some had spent time in jail, some had lost children to family violence, but each taught what forgiveness sounds like when they held me in a circle with their voices soaring in a Maori hymn of peace.

Leaving Vaughan Park was harder than leaving my career. Yet in some ways I never really left. I’m still learning to live between the tides, still listening to the song of broken shells unfolding in a prayer for peace. The conversations I’ve become part of are like so many I joined at Vaughan Park. One of those conversations was the history of an adult faith centre in Sydney, Aquinas Academy.

‘It doesn’t feel finished,’ I told Michael Whelan, the Marist priest who invited me to write the Aquinas Academy story.

The stories are never finished. They are only given back to the ocean like the shells at high tide. Sometimes the stories have been hidden, covered up by an institution in the false name of security. Those stories, too, are carried by the tides. Sometimes the stories, like the monks’ kimonos made into a wedding quilt, are stitched out of silence into blessing. I will keep listening to those prayers.

©Julie Thorpe

Image Sally Longley

-

To be, or not to be...

The sun is setting on Assynt, in the North West corner of Scotland. Orange light warms a cold April. The mountains, Suilven and Ben More are iced with peaks of snow. Feathered friends make a snuggery, while a glistening otter gallops up the slipway with a wriggling trout in its mouth, its rainbow fate sealed. The white-tailed eagle has hovered over the loch for a day, searching for a salmon that escaped from the farm. Just when she smelt freedom, this god of the air snatched her away. So many worlds spin in pain.

At Cape Wrath, angry in the quietest weather, the Ministry of Defence carry out military exercises and propagate the news that they are also preserving the wildlife, flora and fauna of this special place. Meanwhile submarines creep into sea lochs doing what they do. Is there any place on earth not compromised by humanity?

I walk beside the stone remains of townships long since abandoned, kinship fragmented because of greed. Roofless churches in these parts tell the story of an ecclesiology and its earnest guardians who preached a misplaced morality and threatened doctrinal punishment and excommunication. The clergy banished the original spiritual beliefs of the people and yet somehow, the early Celtic Christian movement which managed to weave holy place names and traditions into the fabric of indigenous belief, survived. Over the centuries, many have heard an ancient song and harmony.

‘April is the cruellest month’, writes the poet, T. S. Eliot. Especially so, as we hallow the memory of New Zealanders and Australians killed in war. Such remembering is gathered to our hearts, not to glory the indescribable carnage of war nor gloss over the brutalising and crushing of the human spirit. We do not gather the dead and dying, the grief and sadness, the memories, stories, tragedies, the comradeship in life and death, to dis-member them. Rather we re-member them. This is restorative, moving us, not only to give thanks for the gifts of life and freedom which we take for granted, but to bring to birth, in our own hearts and lives, a harvest of goodness, justice and peace.

Every Sunday morning before going to Church, I listen to Sunday Worship on the radio while eating a breakfast of poached eggs on toast. Today the service was broadcast from Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, the town where William Shakespeare was born and lived and the church in which he was buried.

He died 400 years ago on the 23rd April 1616 and throughout the world, words, music, art and place honour the legacy of probably one of the greatest writers that ever was. William had a lot to say about war: its legal, ethical and religious justifications, the ties between church and state in promoting and waging war, the costs to humanity, and the political strategies used to downplay internal problems and unite a nation around a leader whose legitimacy is in question…’ to busy giddy minds/With foreign quarrels’[i]

He also knew the devastation of grief. His only son, Hanmet died at the age of 11. We know little about his faith yet he writes in The Winter’s Tale, ‘then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written, Death is swallowed up in victory’. He also knows the inner voice of doubt, ‘Ay, but to die, and to go we know not where’.[ii] Resurrection, the deepest hope for our common humanity, was often in his mind. Lives could also be changed because of love, loyalty and miracles. [iii]

I made a visit with my late father to Stratford-upon-Avon in my salad days.[iv] Days when I thought that the ancient houses were higgledy-piggledy and the very fat swans on the river were hungry. I fed them and they obligingly ate what they were given. Dad took me to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre and we drank hot chocolate with lots of cream on top.

I cherish a tiny leather book of quotations from Shakespeare’s plays which he gifted to me on that day. I did not understand the words then. Now I realise that the Bard’s words are embedded in our language…

The course of true love never did run smooth[v]; For goodness sake[vi]; Neither here nor there[vii]; Eaten out of house and home[viii]; A wild goose chase[ix]; Too much of a good thing[x]; The world’s mine oyster[xi]; Not slept one wink[xii]; Send him packing[xiii]; Own flesh and blood[xiv] ...and so many more.

On this Sunday evening, snow is lightly falling as I look out of the window of the Clergy House. Jonathan Livingston Seagull and his partner roost on our roof after spending the day making a home for their young. They are our guests every year and we welcome their wisdom:

Don’t believe what your eyes are telling you. You have to practice and see the real gull, the good in every one of them, and help them to see it in themselves. That way you’ll see the way to fly and that’s what I mean by love.[xv]

©Hilary Oxford Smith

April 2016[i] Henry IV

[ii] Measure for Measure

[iii] Sunday Worship BBC Radio 4, Sermon by the Rev. Dr. Paul Edmondson, Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

[iv] Anthony and Cleopatra

[v] A Midsummer Night’s Dream

[vi] Henry VIII

[vii] Othello

[viii] Henry IV

[ix] Romeo and Juliet

[x] As You Like It

[xi] The Merry Wives of Windsor

[xii] Cymbeline

[xiii] Henry IV

[xiv] Hamlet

[xv] Jonathan Livingston Seagull, Richard Bach -

The I and Thou of Caring

The Stoics of antiquity (2500 years) ago said: To know calmness in life, disengage yourself! Don’t allow yourself to know the extremes of emotions that beset humankind.

My understanding of Jesus’ life in contrast is ‘be open to the wounds of humanity’, and even more than that ‘be open to being wounded by humanity’s agony for in that you will become more fully human’.

We often accept the ‘other’, our neighbour, only if it does not threaten our own sense of individual happiness. Communion and otherness: a call into deeper intimacy and yet also the impulse to flee from the other. As John Zizioulas the orthodox theologian says in his book, “Communion and Otherness”, in Christ “we are called into a movement towards the unknown and the infinite” of the other, and also ourselves. This call into freedom is not only from what has held us captive, but also into what we both can become.

Is this not a paradox that is too much to understand? For if this is true, then how do you carry another’s wounds without becoming wounded yourself? Are our own wounds not enough to deal with, without having to reflect on another? If I offer all of myself to you, then who am I left to be?

This is an important question for us who work in a caring of others, whether that be to our family, our work colleague, or friends or even those we are not sure of, those who may be our enemies?

Well, first, in Christian spirituality, there is an understanding that unless I offer of myself, the “I’ in ‘who I am’, then I will never become truly ‘I’. It is in my meeting with your ‘Thou’, that I come to know the ‘I’ in me. But second and equally, if I give all of my ‘I’ away to ‘Thee’, then I lose my identity, that which is at the centre of ‘I’.

So can we remain truly objective in our care of another? I think not for we are drawn into their story. We do not remain just a witness to their unfolding story. Family Therapy, being anchored in the systemic tradition, suggests we will no matter what our inclination is, become part of the therapeutic circle, and cannot fully remain ‘meta’.

So back to this paradox that is too much to understand! How do you love so you bleed, but not become a corpse yourself? How do you love passionately, but be prepared to let go with that same love?

I really don’t know if you seek an absolute. But I offer this; first it must be to do with truly listening. In the meeting between ‘my I’ and ‘your Thou’, can I discover the God who connects us to the ‘unknown known’ in ourselves, my neighbour and in that who we have given the name of God to? In listening to each of these truly well, I may join a dance that allows me to hear the whole of life’s calls, not just one part. It does not have to be ‘me’ or ‘you’, but maybe ‘us’. Second, by forgiveness, of yourself and your neighbour who has hurt you! Forgiving yourself often for recognizing in life there is no perfect blueprint for your life; you are human and you already have enough to bear without carrying guilt that has long been forgiven by God.

“To listen deeply

to another is to care

To choose

to be so empty of self

what true communion may take place.

Who’s empty?

Few only.

To listen profoundly

is to be still inside

that you may hear

the flicker of an eyelid

or a heart

about to open

like a flower

in Silence.

The greatest revelation is stillness.[i]©Iain Gow

Image Wikipedia Commons[i] Lao Tzu, quoted in Snapshots on the Journey, Rod MacLeod, 2003

-

Living the Sustainable Life!

There remains then a Sabbath rest... let us therefore make every effort to enter that rest, so that no-one will fall. (Hebrews 4:9)

France and New Zealand have two things in common. When I lived in Paris, a long time ago, suddenly in August everything became very quiet as many left Paris for the holidays. Here in New Zealand the same thing happens, but in January; everyone leaves for their batches (holiday home).

For those of us who live in the Southern hemisphere, it is a reminder that as we re-engage with work again, to see our engagement with the new work year as a marathon, rather than a sprint. What do I mean by that….

I was once a surfer, not a very good one I hasten to add, but I had been told it had a certain allure with the young ladies, and at 14, becoming more alluring to them was very important, especially if you were a scrawny shy looking fellow who needed all the help that was on hand possible!

Anyway surfers understood intrinsically something I now call ‘the wave theory of time management’. We didn’t call it that back then, as there were not many models or theories of management around, but it should be called that today, and I suggest it to every organisation’s personnel department! So what is it all about?

In South Africa, waves came in around sets of six waves. There was then a lull, and then on came the next six waves or so. In those first six waves, you grafted hard; it was intense and full on. But then came the lull and you chilled; looked at the beauty of creation all around you; you caught your breath, chatted to your friends, and let your inner voice catch up with you. Then on came the next set and it was back to grafting hard.

What I have called the ‘Wave Theory of Management’ actually was once called the Sabbath principle. God in the first page of the Bible, theoretically knew all about this principle, for having worked really hard for six days at making Creation, then chilled on the seventh. Ever since then, observance of the Sabbath was an important principle; that is until the last fifty years when our more hectic modern life-styles have made it redundant.

Now I am not a believer that the Sabbath principle means it has to be Sunday, but I do believe it is an important principle to leading a sustainable life. Alongside many work-psychologists today, I suggest that we are subtly becoming less human, that our work productivity is less, and our ability to read complex situations when they arise impaired, all because we don’t make the Sabbath principle part of our life. I know this for myself when I burned out for six months around 13 years ago from working too many long hours.

The Bible is not against hard work. In fact it understands how work offers self-esteem and well-being; but Christian spirituality equally encourages a sustainable led life, time for hard work, time for play, time for our spirit to be nurtured. If your life is cluttered with too much on, then you may get on by for a while, but in the end you will become less human, for yourself and for those you love.

Finally, here is another final reason to make sure the Sabbath principle is in your life. You may get by running fast for some period of time. But every so often, as though out of the blue, came a monster wave when we were surfing. We called it the ‘backie’ and it didn’t fit into any rhythm or pattern. If you hadn’t taken the time to take those moments of rest between sets, then you would never have the energy to get to the monster wave before it overpowered you as you desperately tried to swim through it. Likewise, in our life, the ‘backie’ can suddenly happen with the sudden illness of a family member,

Now that most of us are back from our holidays here in the Southern Hemisphere, be aware that the whole year stretches ahead of you. Discover a right cadence for yourself now before the monster waves of 2016 come towards you. Incorporate the Sabbath principle into your life, in whatever way that might mean for you.

I end with a quote from an old saint who once said, “if you cannot make solitude your friend, then you will never hear the wisdom of God for yourself or others...the voice of God that encourages and guides you, the inner voice that nurtures your soul.”

©Iain Gow

Image Surfers at Big Bay, New Zealand, Flickr, Creative Commons 2.0

-

From Glastonbury to Iona

Holidays often begin in weariness. Everyday mundanities soon give way to tantalising glimpses of a different life.

The ferry left a misty Oban and arrived at the jetty on Iona where the weather turned bright. Wild and remote, the villagers of this tiny island in the Atlantic Ocean know how to walk against the unbridled wind. Yet in what has been a curious summer of weather, the sun shone for longer than a day and my skin glowed. Freckles became uncountable.

I discovered coves and caves for the very first time, dreamt of ancient legends that spoke of truth and possibility, walked across fertile flowered machair and awoke at dawn to the rasping sound of grey and chestnut plumaged corncrakes, secretive visitors from Africa. They opened my eyes to the illusory rising of two suns.

The Bay at the Back of the Ocean, the Hill of the Angels, the Gully of Pat’s Cow, the Port of the Marten-Cat Cliff, the White Strand of the Monks and tide-dancing for tiny polished beads of serpentine at Columba’s Bay, beckoned. Ragged robin, St. John’s Wort, bog myrtle and orchids grew in a landscape of translucence and light.

I stayed at a small island hotel. The bread-maker rose early in the morning to prepare her gift and the smell of earth’s fragrance wafted through the house. Fresh organic bread, rich and moist, full of seeds and nuts, carrying the gentle life and death secrets of grain.

The Abbey remains the summer-hour destination for coach weary day-trippers and those escaping the noise and grime of city streets and isolated urban spaces. They come to a remote place and feel at home. At sundown, the island gives itself back to resident dwellers while kittiwakes and sea eagles, like sentinels, soar around this thin place.

When St. Columba made his bittersweet landing on Iona’s shore, the story goes that he chose it because he would not be able to see his beloved Ireland. Drawn to a world beyond his knowing, Columba’s home-sickness must have been like the ache of an uprooted plant with only courage and faith to hold it up. He became grounded in new soil.

And so on to the opalescent mist of Glastonbury, popularly known for its music festival of Vee Dub tents, welly boots, boho, wild flowers in the hair, mainlining acts and mud.

This is Camelot, the Isle of Avalon, a place of disappeared kingdoms, myth, intentional well-being, religious and New Age pilgrimage. Sitting amongst the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, in the drizzle of a mild September day with the ‘once and future’ King Arthur and his wife, Guinevere, reputedly lying buried nearby and with centuries of fireside storytelling warming my imagination, I felt as though I was searching for the rainbow’s end.

Legend has it that Joseph of Arimathea, the great-uncle of Jesus, who placed his nephew’s body in the tomb after the Crucifixion, later made his way to Glastonbury with eleven companions, bringing with him the Holy Grail, the cup used at the Last Supper.

Glastonbury was once an island. It can be seen from a great distance because of the Tor, a hill of some 500 feet, crowned by the 14th century Chapel of St. Michael. Joseph is said to have buried the chalice near the Tor and to have founded the first Christian church in Europe at this Place of Dreams. Resting on Wearyall Hill, he stuck his staff into the ground where it miraculously took root. The Glastonbury Thorn blooms each Christmas.

Great saints over the centuries, Dunstan, Columba, David, Bridget, Patrick and others have journeyed to this sacred and mysterious place as have so many of us ordinary mortals before and since, because not only did Joseph of Arimathea walk there but also Jesus himself.

The mystic, artist and writer, William Blake toyed with that possibility when he penned in his poem, Milton, some verses which became known as the hymn Jerusalem,

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England's mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England's pleasant pastures seen?What happened in this place of unravelled threads?

Richard Bach, author of Jonathan Livingston Seagull wrote, ‘not being known doesn’t stop the truth from being true.’ A rainbow coloured the Avalon sky in the late afternoon. I knew that I might never find its beginning or its end. It matters not.

©Hilary Oxford Smith

Image The Tor, Glastonbury, Hilary Oxford Smith

-

Northern Lights in April

Travelling is in the DNA of most New Zealanders. Over a million of them live overseas and thousands holiday around the world each year. Families love nothing better than packing up the tent, caravan or camper van and hitting the road to enjoy some R and R. If you’ve got an iconic V Dub, all the better.

Clive and I are currently working in Scotland and have been missing the camping adventures that we enjoyed in New Zealand. A wee camper van has now been added to our life and after Easter, we set off on a tiki tour…

By the lakeside at Windermere on an April evening, the water mirrors the still sky. Trees are not yet in leaf. Buds await with quivering intensity. A few boats are about. The day has been one of hot sun and a cold wind. Late snow fell on Helvellyn in the early hours. The daffodils, so redolent of this rugged and wild landscape, are in their dying days.

Nesting for endless hours in the reedy bank is a cob Mute swan. His mate has been swanning around all day looking for food. Non-native Canada geese honk here and there. Conservationists say that they are compromising the habitat and need to be ‘managed’. Waterskiers on the lake fall into the same category.

William Wordsworth wandered here, lonely as a cloud o’er vales and hills. Daffodils inspired him to write some words which have earned themselves a place in popular poetic consciousness. He wrote better poetry though. Mystical, spiritual poetry, most of it, glimpsing divine unity in all living things.

When the rain teemed down and made the black slate houses blacker, the far distant mountains sang ‘the still sad music of humanity’ he wrote. When he felt the loss of that visionary light, his ‘Ode on Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood’, revealed that the memory of it never left him.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a friend of his wrote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner at the village of Grasmere, a place described by Wordsworth as ‘the fairest place on earth’. Like so many of his contemporaries, Coleridge was addicted to opium, commonly prescribed then for everything from a cough to vague aches and pains. He scribbled Kubla Khan after dreaming of the stately pleasure-domes of a Chinese emperor.

Another Lake poet, Thomas De Quincey wrote an autobiographical account of his addiction, Confessions of an English Opium Eater which became an overnight success. The opium dreams did not last for these poets of the Romantic School though. Such imaginings may have presented them with unique material for their poetry but it gradually took away from them the will and the power to make use of it.

There are two villages called Near and Far Sawrey. Between the far and the near, is Hill Top, a 17th century farmhouse that brought the kind of childlike imagining I had put away. Beatrix Potter, the writer and illustrator bought the property with the profits from selling her first book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, written first as a picture and story letter to cheer up a five year old boy who was ill.

Most writers have to learn to deal with rejection at some time or another and she was no exception. After several snubs from publishers, she finally landed a publishing deal for the story of this rebellious rabbit.

Potter’s own remarkable tale was that of a young woman who finally freed herself from demanding and possessive parents and achieved independence and fulfilment by her own efforts. The farm became her sanctuary, a place where she could draw, paint and write about lovable and villainous anthropomorphic animals and the triumph of good. Her stories are not only for little children.

And then on to rural South West Scotland and the ordination of a good friend. Farms and houses are scattered far and wide in his new parish and I was reminded of the 18th century diaries of Norfolk clergyman, James Woodforde who led an uneventful and unambitious life except that for 45 years, he kept a diary chronicling the minutiae of life in the parish. His was an endearing pastoral ministry by all accounts, that went hand in hand with a liking for roast beef dinners washed down with copious amounts of claret and port and always shared with friends. His legacy is a jewel of a diary that illuminates the darkest of times.

Wordsworth worshipped at St. Oswald’s Anglican Church in Grasmere. He found it a comfortless place apparently. I can see him sitting on a hard bench, his feet on the earth floor which would have been covered with rushes, with the only heat coming from a tiny grate in the vestry, burning wood and charcoal. In his later years he warmed to the church when he wrote Ecclesiastical Sketches, a history and defence of the Anglican Church. He had grown to like its moderation and tolerance which he regarded as its strength, tempered through centuries of conflict and trial.

In the churchyard at St. Oswald’s, lie his remains and those of his wife Mary, sister Dorothy and his children, Dora, Thomas and Catharine. The poet Harley Coleridge, son of Samuel Taylor is also a neighbour. Alfred Lord Tennyson said that ‘next to Westminster Abbey, this to me is the most sacred spot in England.’ He may well be right.

©Hilary Oxford Smith

April 2015Image Northern Lights at Bow Fiddle Rock, Portknockie, Scotland. Alexander Dutoy

-

Northern Lights in June

A New Zealander arrived on our doorstep last week, cold and alone. The early British summer had finally got to him. The Manse, which is the Scots name for a clergy house, was marginally warmer than the temperature outside.

When we lived in New Zealand, my memories of childhood summers in Britain were building sandcastles on the beach, eating ice-cream with sprinkles, skipping through fields of daisies, being an imaginary fish in the sea. Now I remember what I had chosen to forget. That it all happened in the cool wind and rain with glimpses of sunshine.

Our Kiwi friend, who is discovering his family history, was en route to the Orkney Islands, that archipelago, far north. Weather forecast grim. The Orcadian Sabbath is a day of rest, he said. Nothing to do except go to church. Which he did, at St. Magnus Cathedral. Afterwards he read The Observer newspaper, from cover to cover in the relative warmth of a B and B in Kirkwall.

The Cathedral, one of the finest medieval churches in Europe, is known as ‘The Light of the North’, founded in 1137 by the Viking, Earl Rognvald in honour of his uncle, Magnus. Thereby hangs a saga of political intrigue and dirty deeds. Since those early days, the Roman Catholic, Norwegian, Scottish Episcopal and Presbyterian Churches have all claimed the building as their own. Yet the Cathedral has never been the property of any of them. It belongs to the people, assigned to them by King James III of Scotland in a charter of 1486.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, there have been baptisms, confirmations, a wedding and funerals. We yearn for markers in the transitions of life. This is where the Church comes into her own, offering an embodied love through the rites of passage that give meaning to the passage of time and experience.

Another kind of embodied love is happening at the Findhorn Community which beckoned me earlier this week when the sun came out. In the swinging ‘60’s, Eileen and Peter Caddy and Dorothy Maclean found themselves without work.

With their children, they lived in a caravan on a wild and windswept shore. Feeding six people on unemployment benefit was almost impossible so they began to grow, from poor soil, amazing flowers, herbs, fruit and huge vegetables. Word spread, botanists and horticultural experts visited and the garden at Findhorn became famous.

The longing of these three friends was to 'bring heaven to earth'. Others joined them in that hope and now the Community commits itself to a sustainable, holistic way of life and a spacious spirituality. I whiled away some time in one of its smaller gardens. Bees were about, water tumbled over rounded stones, carrots and capsicums grew in the midst of late bluebells and old roses, lemon balm, sage and lavender. A lady wearing a floppy straw hat sat in a shady corner, back straight, eyes closed, calming her mind.

Two small and beautiful books of poems and prayers arrived in the post a few days ago. Written by friends in New Zealand, Where Gulls Hold Sway and Be Still were companions on that afternoon of perfect light. The touch of new paper, the smell of ink and glue, the physical turning of the page with thumb and finger, the reading of words that read me…what is this heaven?

Later this month, at Stonehenge, a mysterious formation of stones in perfect alignment with the solar events of the Summer and Winter Solstices, there will be many peoples, who will gather in a spirit of togetherness, to celebrate the Light on the longest day of the year.

In the Southern Hemisphere, on the same date, the Winter Solstice will gift quietude, firelight, restfulness, while seeds germinate in the cold earth. Our ancient ancestors knew the sacredness of such times.

Memory recalls a visit with Clive, to a recumbent stone circle in Scotland with the almost unpronounceable name of Easter Aquhorthies. It happened many moons ago, in the early hours of a Summer Solstice morning when we were first in love. We cooked eggs on a makeshift stove for breakfast and then watched the pink porphyry, red jasper and grey granite stones, placed there over 4,000 years ago, change colour in the enchanted light. It seemed as if the whole world was open before us.

The earth spins around, time passes in minutes and millennia. We come, we leave, we meet again. One story.

©Hilary Oxford Smith

Image Caithness Croft, Deborah Phillips -

Spero: I Hope

“It was now about the sixth hour, and darkness came over the whole land…for the sun stopped shining.”

The heavy cries of the swooping seagulls fell silent and a chill crept into the air as the Moon came between us and the Sun. The deep shadow, which formed first in the North Atlantic, swept up into the Arctic and at the North Pole became no more. As the recent solar eclipse reached totality and the irridescent crown of the corona surrounded the sun, words from Pádraig Ó Tuama’s poem, In-between the sun and moon came to mind:

“In-between the sun and moon,

I sit and watch

and make some room

for letting light and twilight mingle,

shaping hope…”[1]I first came across this Irish Bard when a writing scholar at Vaughan Park said to me, ‘oh, you must discover him’. So I did. Actively involved with the Ikon collective in Belfast, The Corrymeela Community and the Irish Peace Centres, Ó Tuama gives an earthly and transcendent voice to life, troubles and hope.

The lamps are going out over Syria, reports Gerald Butt, the Middle East correspondent of the Church Times. According to satellite imagery at night, the destruction of 83% of lights in the country has plunged most of this fertile crescent into darkness.

After four years, the war rages on and highly publicised extreme violence by cross-border terrorist groups and the myriad violations of international law and human rights committed on all sides has spread to other countries and engendered fear and atrocity across swathes of the world. Fighting men and praying men lie side by side…their harmony together is found in rounds of fire and occupation. For most of us, what is happening is a scenario too stark, too horrible, too brutal to fully contemplate over breakfast or at any other time.

There are those in the three Abrahamic faiths who preach from lofty heights where the air is cold, that what is happening in Syria is linked to Biblical and Islamic prophecy about the End Times. As they turn a well-thumbed page of The Revelation of St. John the Divine, they confidently propagate their thirst and hunger for Doomsday while ten million innocents have fled their homes, are without shelter, war-ravaged, hungry and thirsty. Many people are not even able to bury their dead.

To mark the fourth year anniversary of the war on 15th March, #With Syria, a campaigning coalition of more than 130 humanitarian and human rights organisations, including Amnesty International, Christian Aid, Oxfam and Save the Children launched a video, ‘Afraid of the dark’[2], calling on world governments to do more to end the suffering of the people.

Thanks be to the people who refuse to let hope die and live Christ’s gift of peace.

“Blessed are the peacemakers for they shall be called the children of God.”

The bones of a Plantagenet king, on the throne some 500 years ago, were unearthed by chance and, watched by thousands, were re-buried within the small and beautiful Leicester Cathedral a few days ago. Richard III died in battle at Bosworth Field in 1485 and his body was buried by Franciscan monks in a simple grave. Leicester City Council unknowingly covered his burial place with tarmac and made it into a car park. Cardinal Vincent Nichols, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Westminster, acknowledged that Richard was not a man of peace. “The time into which he was born, and the role into which he was born, did not permit that. But now we pray for his eternal peace.” History is sometimes seen through a glass darkly. “What is truth?” asked Pilate. “

There are fragments of who and what we are in all the characters and events of Passiontide and Resurrection:

“ The soon –to-be Easter light…

highlighted the night between

our fallings and our flyings

on this Friday of our good sorrows,

or bad sorrowsour mad, and sad,

and

glad that there are gladder days beyond these days sorrow.We toast the night, o felix culpa,

and hide the light of lightsfor a while”[3].

In Scotland, where I am currently living and working, the dying days of winter are giving way to Spring. The heavy rains have almost gone, the flowers appear on the earth, the blackbird sings. Autumn in Aotearoa heralds a different season of colour, of ripening and fruitfulness, where new thresholds and possibilities beckon and emerge.

Wherever we live in the world, can we trust the Easter promise of these openings and unfurl ourselves into the grace of new beginnings?

Jasmine is the symbolic flower of Damascus. In April each year, there used to be a Jasmine festival held there. It still blooms amidst the rubble and fragrances the air.

©Hilary Oxford Smith

31 March 2015Image: www.yesicannes.com

[1] Ó Tuama, Pádraig, readings from the book of exile, Canterbury Press, Norwich, 2012, p. 12

[2] Afraid of the Dark, https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=EWwLzEQazcc

[3] Ibid., Good Friday, p. 16

-

Northern Lights in May

A golden and warm sun rose early on the first day of summer, May Day. The distant hum of a lawnmower reminds me of how much the lawn is part of this country's identity. Think cricket and the sound of leather and cork on willow, cucumber sandwiches and Earl Grey, afternoon strolls around the park, strawberries and cream. Antidotes to unpredictable weather.

It is blowing a howling, living gale outside. Our two puppy dogs think that wolves are about. Ferries have given up sailing to the islands, trucks are travelling by the low road and white horses ride the waves. Rudyard Kipling evoked the destructive possibilities of the sea in his poem, White Horses. Migrants from Africa, escaping to Europe and fleeing from fear, poverty, dispossession, know about white horses only too well. And still they ride the waves every day…some never reach the shore.

‘Be tough on immigration’ say those who believe that a mixture of boat tow-backs and harsh detention centres on remote islands is the solution to stop people smugglers and prevent deaths at sea. The delusional seduction of ivory towers.

In 1915, Kipling’s son, John, serving with the Irish Guards, went missing in action at the Battle of Loos. Kipling later served on the Imperial War Graves Commission and chose some words from Ecclesiasticus, which have been inscribed on many war memorials since: 'Their Name Liveth For Evermore'.

The names of those who died because of the badly planned, ill-conceived and disastrous Gallipoli campaign were remembered here on April 25th as they were in the Southern Hemisphere and elsewhere. After nine months of bloody slaughter, Winston Churchill, the ambitious First Lord of the Admiralty resigned. He lived to fight another day of course, spurred on by keeping a whisky going throughout the day.

The 70th anniversary of VE Day was commemorated last week. A fleeting, heady celebration back then, masking the loss and regret, the dispossession and homelessness, the anger and frustration. Churchill and his Conservative Party were heavily defeated in the 1945 General Election. There is a time for everything and everyone.

Another Conservative Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, apparently read all 845 of Kipling’s poems on a short summer holiday in 1976. It must have been raining. The new Members of Parliament, recently elected in the General Election in the UK haven’t had time to read poetry. The posturing and bargaining has started, superseding news from the far South of John Key’s ongoing Ponytail-gate saga.

Prince Harry though has been basking in the limelight of an Aotearoan sun. With Uncle away, the new Royal baby brightened the nation’s mood here. Charlotte Elizabeth Diana weighed in at 8lbs 3oz. Her mother, Catherine emerged from hospital, a few hours after giving birth, looking beautifully blessed. Her father too. They are sheltering trees where their little daughter’s fledgling heart can rest.

On this Ascension Sunday, I have been asked to christen a baby girl called Emily who was born on the Feast of Stephen. She came into the world, like a Christmas rose, petals unfolding, gentle and fragrant. Her parents’ love and kindness has come into blossom.

If her destiny is sheltered, I pray that the grace of this privilege may reach and bless other children who will be born and raised in torn and forlorn places.

©Hilary Oxford Smith

May 2015Image: Findochty, Sally Gunn

-

Ground for Justice

New Zealand has a history of criminal trials and subsequent resolutions exposing miscarriages of justice. Re-trials, many years after an offence, are becoming almost common place. This may be seen as justice eventually being worked out or, alternatively, a failure of the country’s legal system. Justice may be an elusive ideal.

Crime reporting fills a considerable amount of media content informing an ongoing public discourse. Within such discussion, balanced information and debate is not always as apparent as the immediate calls for public safety and firm punishment. More nuanced debates about causes, appropriate punishment and long term remedies for individuals and communities are often at risk of being seen as failure to confront society’s need for calm and good order.