Writing

-

Spring clean

let me sweep your church

I’d leave the door ajar

to split the glimpses of grace,

remind them who you are.those who peek within

drawn to your loyal side

& you would see without

the futility of pride.I’d stir up with my broom

the dust of fusty pews

service to a servant

a friend they stand to lose.I’d clean the stained glass too

for a little light to shed

in a gloomy, stale state

the vision’s limited.let me sweep your church

I’d fling the door back wide

so you might hear your calling

to stay, or step outside.©Peter Clague

-

Living In A History

We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.[i]

Winston Churchill...what we build will, over the years, shape how we understand God.[ii]

Anselme DimierIn the few months since arriving in Stroud I have increasingly appreciated Saint John’s Church – this building to house the Church. At first sight, my attention is held by three features of the building: the high twin pulpits; the particularly small sanctuary; and the choir seating.

These features cause me to reflect on understandings of the Church and worship at the time of its construction, and where continuities and divergences may be found in both older and also in contemporary understandings and ways.

From my morning and evening prayer seat in the choir looking across to the tall tower for preaching or reading, my eye then travels to the rear of the church. Given the social context of the building of this chapel of the Australian Agricultural Company, I try to envisage what evangelical exhortations and morally improving messages may have been directed from the pulpit to the occupants of the convicts’ gallery. My imagination is fuelled somewhat by the piercing eyes and stern countenance of the chaplain William Macquarie Cowper whose photograph hangs in the foyer of the rectory.

St John’s brings to mind my affection and gratitude for two historical periods, and aspects of church architecture and the liturgy for which it was built. The first is the (largely unremembered) Anglican continuity with Benedictine monasticism. Although monks in their stalls have long been variously replaced by canons and clerks, and by cathedral and parish choirs, the singing and recitation of daily prayer and Sunday worship is carried back and forth from either side of the choir. Then as now, our answerability to each other whilst praying in such a manner remains apparent.

A second facet of my gratitude is being able to pray and shape liturgy in a church which pre-dates the neo-gothic revival in Anglican ecclesiastical architecture. Accompanying this is an absence of unconscious (or perhaps even indiscriminately followed) assumptions and directions in worship largely inherited from the determining architecture of that era. On a practical contemporary liturgical note, I am glad of a single-level sanctuary, rather than the later more usual multiple steps. The pulpits are high, though not the altar! Although I owe much to the neo-gothic influence on my earlier liturgical formation and practice, my more deeply rooted attraction is to the unadorned simplicity modelled by Cistercian monastic liturgy. The relatively undecorated Georgian style of St John’s is happily conducive to the prayer tradition which has most profoundly formed me.

A quotation on the Friends of St John’s Stroud website from architect Clive Lucas describes the church as “perhaps the finest and certainly most intact Anglican [c]hurch in Australia which predates the influence of ecclesiology.” To take gentle issue with this assertion, I would argue that any church of whatever era is an expression (whether by adherence, modification or rejection) of the dominant tradition of the time.

St John’s was built in the year of the beginning of the Oxford Movement and before the subsequent Catholic revival in the Church of England. The ecclesiology of our building thus reflects an earlier piety than that of both the Oxford Movement and also the associated 1845 Cambridge Camden Society, also known as the Ecclesiological Society, whose interpretation of ecclesiology was specifically related to matters of church building. The architecture of St John’s reflects a more evangelical understanding of the Church (ecclesiology) and thus pre-dates the predominant anglo-catholicism of the diocese of which it later became part.

Comments in the visitors’ book often make mention of the historic nature of the church and our other buildings, and also of St John’s being a prayerful and beautiful place. I like to hold this trinity of beauty, history and prayer together. An enduring gift of St John’s lies in enabling visitors and parishioners to allow this meeting of the past to find expression in the present, and to give hope for the future.

Week by week parishioners gather to celebrate the Sunday Eucharist, gathered at the sanctuary built for this purpose in 1833. The steady life-giving heartbeat of the church community is sustained in the daily offering of Morning and Evening Prayer, for the praise of God and to pray for the world and the Church. St John’s Church continues to be a place where the memories of successive generations are treasured, and a place which continues to symbolise the spiritual and community hopes of present and past Stroud people. I am glad to be joining this living history.

©Martin Davies

Image Interior, Saint John the Evangelist, Stroud, NSW, Australia

-

Come Unto Me

Which comes first? Baptism or Communion? Baptism is not a requirement for communion and so I have heard the new PC(USA) Directory for Worship hopes to affirm the free and abundant grace of God we find at the Lord’s table. No exceptions. I have, for some time, embraced an open table and I believe the Church, not only the Presbyterian Church (USA) is opening to the idea of sacrament as welcome and inclusion. I confess that I enjoy worshipping at an Episcopal Church where this unconditional welcome is crystal clear.

Earlier this year I was asked to celebrate an “extraordinary” baptism. Of course, all baptisms are extraordinary, but this would be a baptism that bends the rules, stepping just outside the doors of the church. Sara Miles, in Take this Bread, had already suggested to me the idea of a font outside the doors of the church.

My nephew and his bride grew up in the church, Presbyterian and Lutheran respectively. Like most of us, there have been times when they felt excluded and alienated by the church. They are now young parents, both working hard to balance family, work, and pleasure. They were married by a beloved pastor in the great outdoors, with the mountains as a backdrop. When they began to think about baptism for their daughter, Harper Iona, the doors were closed to them unless they became members of the church. And the font was behind those doors.

They say that young adults don’t think about membership the way we boomers and older folks do. I thought about all the ways the old-line, mainline churches are trying and failing to welcome younger adults. I thought about all the baptisms I had celebrated inside the church, where the parents made their promises out loud, but were never seen again on a Sunday in church. I also thought about the Church of Scotland where I have served, and the way that they have wrestled with this very question, loosening up a bit on the membership requirement.

When asked to baptize Harper, I so very much wanted to say “yes.” My initial response was, I so want to do this, but we would need to figure out a way to make it an “official” baptism. It would not be a blessing or a dedication. It would not be a private baptism. I was willing to bend the rules, but I have become increasingly sacramental over the years. When I asked the parents why they wanted Harper baptized, they had all the right answers. She is a child of God. We want to say that out loud to our family and friends. And, yes, we will profess our faith out loud. And, yes, we will promise to raise her in the church. And, yes, everyone there can gently remind us that we need to find a church. And we will. In time.

So I read and reread the Directory for Worship. And the Bible. And I talked to a few clergy friends in various traditions. And I even talked to a couple of polity wonks to try to figure out a way to do this.

And then I attended another baptism inside the church and realized that very few Sunday morning baptisms follow the Directory for Worship to the letter. They happen before, not after the sermon. There are no renunciations. Hardly ever is the Apostles’ Creed recited by one and all. There may or may not be an elder present. Questions may or may not be asked of the congregation. Session may or may not have recorded it in the Register.

Over the years, teaching Reformed Worship, when “extraordinary” cases in point were raised in class, I always told my students to wrestle with three things: the pastoral, the theological, and the ecclesial. And of course, the Bible. The ecclesial requirement of membership in this case seemed a way of pushing this young family further from the church. I prayed. I conversed. I listened. I read. I wrote. And I decided that I could create a sacramental service of worship that honored the Directory for Worship, but more than that, honored the spiritual lives of this family, Reformed theology, and the Word of God.

Gospel words began to ring in my ears: “Suffer the little children to come unto me and forbid them not, for to such as these belongs the kingdom of heaven.” “Wherever two or three are gathered in my name, there I am in the midst of them.” “God is love, and those who love are born of God and know God.” “Here is some water, what is to prevent me from being baptized?”

So I said, “yes.” And I conducted a service of worship outside the doors of the church, but with a gathered community of family and friends who would sing and pray, who would hear the Word proclaimed, who would respond by professing their faith, and by witnessing the promises of these young parents. Both great grandmothers are elders, so they stood with me as those gathered promised to support this family. Two close friends were sponsors. The only missing piece, in this case, was that the baptism would not be recorded in any congregation’s minute book. I made them a very beautiful certificate and signed it!

It was an extraordinary event for so many reasons. But in the thinking and the praying and the planning and the celebrating, I was changed. A sacrament is a visible sign of an invisible grace. That I have long believed. But a sacrament ought not be a way of excluding anyone from that invisible grace. A sacrament ought to be an invitation, a welcome, a reaching out, evangelism. We can no longer wait inside the church, behind closed doors, waiting for young families with children to push their way in.

I am honorably retired, so not as worried as I might have been a few years ago about breaking or bending the rules. I know that I am way more “by the book” than so many younger, edgier pastors who would say, “What’s the big deal?” By narrating this event, I am refusing to fly under the radar. I am professing a scruple. At least. So defrock me.

We are sacramental. I am a Minister of Word and Sacrament. A priest. We are to tear down the fences and the dividing walls. The doors of the church ought to be open. Always. So, if I believe in an open table, where all are welcome, baptized or not, then I believe in a font that is right there, right near the open doors of the church as a sign of welcome. As a visible sign of invisible, lavish grace. And filled to the brim. Always.

©Rebecca Button Prichard

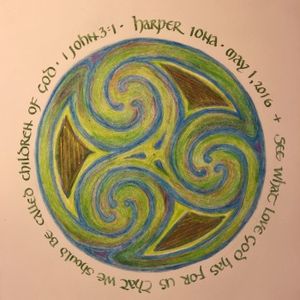

Image Baptism Certificate made and gifted to Harper Iona and her parents from Rebecca.

www.rebeccaprichard.com

-

The little anglican church

In the nave

two chairs with arms

look at each otheron the

trail of window sills

queen anne’s lace

stencils

sun and shadowabove the altar

a collage of local

hills and houses

church and local theatre

train at the stationthe place I get off

is where love

and grief collide

just a feeling

insidewhen the Shepherd

comes looking

for me

when His heart

calls

i’ll run

the road

of paradise

won’t look

behind

ends

©Tess Ashton

Image Marc Chagall (1887 – 1985) Song of Songs IV -

Hill and tree poems

i

A church and a bellI’ve seen a tree on a hill

(with a church and a bell)

out my window

for 17 years now

alone without leaves

I now realize

must be dead

from this side of the river

who knows

yet says

‘I stand for all

things set apart

by those with an eye

for things placed

on a hill

or a table

for contemplation’

and I realize

it’s a dead tree talking

warming the living

saying love

is complete

in all things

givenii

Hungerwhen i look at the

tree on the hill

with the church and the bell

and the river in front

and the bush

on the edge

of cloud-touched tracks

the slow-moving rhythm

of the sky above

a poem no less

with a train

running through

but what is a poem

but truth coming forth

like Heidegger’s

butterfly

or a moment

of leaving from

a railway station

the crying most often

i come to the

hill sounds the call

for children

hungry and dying

how best to help

where are

they exactly?a feeling below

of small hollow boats

on long empty rivers

forgotten then

sailing then lifting

on rainbows

children and babies

no fanfare

or tombstonesiii

Yang Yang and the view from the backAbove the tree on the hill there’s a Catholic

church with woods backed up facing

us Off the flat ‘burb road from

the cul de sac entry

there’s a school

attached

too I

haven’t

seen lately

What the kids don’t

know there’s a hill stretching

downwards to a pink-blue river sky in its

mirror On the back of the hill the sun comes

early shifting things in the dark with

light across pasture Think often

of ‘yi yi: a one and a twoa movie that speaks

of forgotten

views A boy

with his camera

clicks heads from the

back says we all need help

with the tracks we’re immune to

On Sunday went swimming in singing andsermon and movie and river and light on hill

gliding caught the rear view from

Colossians too the wind of

the Spirit showed some-

thing odd though

a cloud of my

making

jiggled a warningShamed to name sins

that cut into focus Today

stroked the back of a neck of a loved

one felt the scar where hearing was taken

forever Clever Yang Yang to spot a least thought about angle

iv

The days and nights of Manapau Stblue

pink blue

blue orange

orange black

black blacksets the red station light

moon of the train

the bridge and town

alight in the distance

clack clackas the train goes by

with the river

and clouds

who’d move?

relax relax

you might touch God

it’s paradise

here

in the cosy ‘burb

most times most times

and the hills over there

and the river

in front

and lights and city

in tiny perspective

this place this placehere clouds

and people

stride together

the old troll bridge

to catch the train

to town to townpast our verandah

meander the station

the edge of the

platform

the way of the journey

so near so nearMeadowbank kids

perch in formation

itching til airborne

bedrooms like hurricanes

ducks going somewhere

lift off lift offby tides and timetables

hearts spin back

to days and nights

of pink and blue

and orange and black

think back think backv

Fool on the hillouta that scene

for good

rear view

mirror

tells a story

giant sun

proclaiming

glory

not disaster

on the hillhome alone

rays bear down

deepest

heaven

four years

rot

dug out

in twenty

minutesnervy dream

old scene

naked

In the elevator

heading for

the upper

floor

be still

hints

St Francisnext day

wander to

garden centre

a rose

my name

chosen for

spring promotion

heart felt

description

swirl of love

birthday gift

from heavenly

Father©Tess Ashton

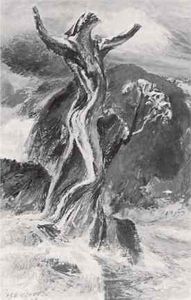

Image The Slain Tree Eric Lee-Johnson c. 1945, Auckland, New Zealand

-

On ANZAC Day

In 1941, when Japan entered the Second World War, the Marlborough Sounds, which makes up a fifth of New Zealand's coastline, was considered to be vulnerable to possible invasion. In the tiny, scattered settlements along the coast, a Home Guard, made up of women and men protected the sea and land as best they could.After the war, the Home Guard Games were held each year in the Western Sounds, so that those who had served in home defence and their families could meet, free from the threat of war. Now known as the Te Towaka Sports Day, local people still gather to enjoy time together.On Easter Monday, we enjoyed one of the most beautiful and awe-inspiring drives in the world to French Pass (Te Aumiti) in the Sounds. The road there, still largely unsealed and treacherous in places, was only completed in 1957. Between the headland of French Pass and D'Urville Island is a turbulent stretch of water. As the tide drops, a massive amount of water, banked up in Tasman Bay, gushes out to Cook Strait. When the tide rises, it rushes back in. With powerful currents, eddies and whirlpools, it is a passage feared and respected by mariners as well as being an area rich with the presence of dolphins, seals, orcas, seabirds and other marine life...a microcosm of the Creator's beauty and life.On the way to French Pass is the township of Havelock. When I was working as a journalist I came across a small boat moored in the harbour there, called Seagull. I subsequently wrote up her story for the newspaper. Now one hundred and nine years old, this trusty vessel went to Gallipoli on the hospital ship, SS Maheno. Anchored off the island of Lemnos, she operated as the ship's tender. With her brave and steadfast crew, she transported wounded and dying soldiers to the hospital ship. Her war service is recorded in the Royal New Zealand Naval museum. I have no doubt that the echoes of dismemberment, pain, suffering and deliverance still echo around her bulwarks. She has surely earned her quiet retirement.ANZAC Day on both sides of the ditch, seems to generate, somewhat ironically, the expression of conflicting viewpoints and ideas about what the day is really about. Isn't it though, a day to tread lightly, to be compassionate and to remember, with sorrowful love and gratitude, the ones who went to war in the paradoxical cause of peace, those who have lived and still live with loss, separation and lasting injury of body, mind and spirit since and all the countless others who have been and will be, on this very day, the civilian and military casualties of war?This year is the centenary of the beginning of the First World War. It was to be the war to end all wars. Yet in spite of the now widely acknowledged military blunders and the unimaginable loss of life, the history of the world tells us that there will always will be those, who with a deep paucity of spirit, want to dominate others and use whatever means at their disposal to fight for ultimate power and possession. Conversely, there have been and always will be the people who work tirelessly to resist such agendas, the ones who restore and reconcile and make peace.Amidst the discussions about the significance of ANZAC Day, which should be rightfully explored but not only in the few days in and around the 25th of April, the suffering and loss of so many can never be allowed to be buried in our memory or the national and world memory.It is decent and honourable to commit ourselves anew to creating a world in which all that is good and precious and shining will grow and flourish. What is ultimately remembered on ANZAC Day or on any Remembrance Day come to think of it, is, I want to suggest, not actually patriotism, jingoism, the glorification of war, the expression of nationalistic fervour. That is, arguably, a kind of easy reductionism. What is deeply remembered in the individual and national consciousness is the indiscriminate slaughter of humanity, the quiet dignity of the human spirit, the gold that is buried in the ground, the longing for peace, the sanctity of life, the indestructible power of love.Some of my family and friends served in the civilian and armed forces at home and overseas in two world wars and in other conflicts since. I have come to know as the years have gone by, that in spite of their own misgivings and apprehensions about the architects of war and the reasons for and consequences of war, they and others have much to teach us about courage in the face of fear and death, humility and strength, vulnerability and loyalty, endurance and suffering, peace and love.As we continue to reflect upon issues of nationhood and identity which appear to be intertwined with the commemoration of ANZAC Day, we might also reflect upon how we can become peacemakers in our own circles of life, for peace begins with you and me. The Church also has to be willing to prayerfully and demonstrably grow into a visible unity and be a sign of hope to our often divided world. It is easy to preach and pray about peace. The tough call is to make peace and live in peace with one another every day. That is altogether a much greater challenge.©Hilary Oxford Smith25 April 2014ImageCarillon, William Longstaff, National Collection of War Art, Archives New Zealand.During the course of the First World War, the New Zealand Expeditionary Force suffered 59,483 casualties of which 18,166 were fatal. Will Longstaff honoured the New Zealand fallen by painting a scene depicting the spiritual images of soldiers gathering on the beaches of Belgium and listening to the carillon bells in their home country. The painting is permanently housed at Archives New Zealand, Wellington, New Zealand. -

Bread and Wine

1.An English cathedral on a summer Sunday morning.Sunlight shafting downwards through the stained glassonto the choristers, whose ethereal music soars heavenwardsto the high vaulted roof above.The bishops and clergy are bedecked in their finery,rich reds, green and gold,dressed as if to attenda Celebration.The service proceeds to its climax,the congregation moves slowly forward,slotting into the spaces at the altar railto receive the bread and wine,then tiptoeing back to their placeshumbled, yet uplifted.2.A Scottish Presbyterian Church on a Sunday morningat the sacred hour of eleven.The congregation gathers early.The atmosphere is graveas they sit in silent expectation.The elders enter, dressed in sombre colours,(save for one, an exiled Anglicanin whose memory the idea of celebration still lingers on,and whose red pullover glows like a living emberin a dying fire).The service is solemn and dignified,sounding the twin themes of death and resurrection(though a stranger could be forgiven for thinkingthat to many present,only the first half of the message has got through).The miracle isthat God is able to break throughthe trappings and the ceremonyand reveal Himselfto those who seek Him.3.A Methodist Chapel, small and friendly,still with a historical hangoverfrom the temperance movement,so serving strictly non-alcoholic wine.And since that liquidhas no anti-bacterial properties,the common cup has been reluctantly discardedin favour of glass thimbles.The service is simple but expressive,each person invited to the table, pew by pew,coming forward as a symbol of freewill,kneeling as a sign of unworthiness and reverenceto receive the bread and wine.And afterwards, still kneeling,words to strengthen and encouragespoken by the Minister as he sends his flockback into the world to share with the worldwhat they have received.4.Four friends meet in a house for a meal,brought together by a common grief.One, a non-believer, brings as a gifta newly baked loaf of bread.Another brings a bottle of wine.The meal is eaten, the wine is drunk,and memories of those not present are tenderly recalled.There is talking and listening,sharing and caring.God is never mentioned,but He is there.©Margaret LyallImage Bread and Wine, Sr. Mary Stephen CRSS -

Spacious Spirituality

You will not have to travel far to appreciate the multi-cultural character of Auckland and much else of New Zealand. The diversity of cultures is obvious at work places, parks, beaches, schools, streets, malls, markets, theatre, wherever people gather and pursue the demands of everyday.In the life of my generation contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand has relegated a white monocultural society to the historical record. While far from perfect in current form, there can be no return to an era when immigrants were tolerated and indigenous people were seen rather than heard.New Zealand is now recognised as part of the Asia region. A small, independently minded South Pacific country making its way in a competitive rapidly changing world. Globalisation and cultural diversity has become the modern reality.In any society, New Zealand being no exception, the need for cultures to understand one another and commit to sharing the benefits of living alongside one another has never been more pressing. Prejudice about differences of race, social status, religion or outright xenophobia will lead only to destruction of mutual wellbeing.The history of world religions provides many examples of such destruction and the record continues to grow. Tragically, conflicts categorised by religious difference remain flashpoints for violence in many parts of the world.This reality has increasing significance for the Christian Church internationally and within New Zealand. While it is often argued Christian values inform our law and culture, multi faith dialogue has long been promoted by many Christians.Over time many other religions have taken firm footing, bringing differing expressions of spirituality. Sadly this can threaten the confidence of some about the perceived place and/or status of the Christian Faith.Chaplaincies minister at the raw edge of this reality. School, military, police, hospital and other work place chaplaincies are all examples, ministering in places where people present a variety of faith expressions or none. Parish clergy, too, minister in communities with incredible diversity. Ministry is not as straight forward as it once may have been.The immediate response is the Church ministers to all. Thankfully this remains true. However, there is a point when differences between religions can become a barrier to sharing the experiences of spirituality.It is not unheard of for Chaplains and others to find themselves needing the generosity of a spacious spirituality which recognises the validity of another belief and faith system without needing to compromise their own. I recall a Biblical scholar describing a “proper confidence”, namely the capacity to defend one's faith with strength of gentle reverence. I also recall a senior Anglican Priest once said to me, tell me a more convincing story and I will accept it.A spacious spirituality has room to accommodate dialogue and respect for differences of belief and faith. Other religions notwithstanding, a simple test is to listen to the almost incredible differences of belief held across the spectrum of faith within the Christian Church.The world is changing around the Church. The Anglican Church's tortuous response to sexuality issues is illustrative enough. Yet, after years of struggle, much of the Communion is beginning to express a spirituality once considered virtually an anathema a generation ago. Theology is clearly responding to societal change: it always has done.The challenge pressing the Church is how to live with other religions in ways that authentically share the human experience of spirituality. Avoiding or attempting to control such challenge will serve to deepen conflict and hasten the unnecessary decline and marginalisation of the Church. This is a loss not merely for the Church. Rather it is a failure to address the diverse nature of human need with generosity of Spirit that defines the practice of Faith.©John FairbrotherImage by Colin Hopkirk -

The risky path of engendering conversations

Sunday morning is a day that retains vestiges of being a day set apart. A great day for attending systematic attractions geared to meet the voracious engine of retail need. Yet, do you sense a faintly different ambience to other days of the week?On Sunday mornings garden centres, malls, cafes and the like are busy. The phenomenon of shopping has become a fixed ritual in New Zealand society. For those who can afford the luxury, Sunday is a great family and friends' day with all this country offers with retail, alongside the traditional enjoyments of arts, sports and scenic locations.Each Sunday, a living relic of an era now passed continues to exhibit life signs. Around the country there are gatherings of Christians of all sorts of theological persuasion. Such gatherings continue to fall under the public classification of Church.Within current life-time church attendance was once among the main public activities of the day. That reality authenticated the day's name and style. Sunday was the recognised, established Christian Sabbath, the one day of rest available to the majority of the population in each week. Clearly neither remains the case.Goodness knows churches have tried to hold their numbers. The Anglican Church, for example, declared the 1990's to be the decade of evangelism. If numbers were to be the measure, success was distinctly limited. The same Church retains a fivefold mission statement that, fortunately, manages to release an occasional glimmer of light.Many churches have applied all sorts of programmes to attract and disciple possible returning and new adherents. For example: there has been 40 Days of Purpose, Alpha, Messy Church, and Progressive Church, support for ongoing clergy development and systematic learning opportunities for laity. Meanwhile some have sought to quietly evolve the long familiar practice of customary Church. To date the overall decline is showing no sign of arrest. Sadly, perhaps, talk about the Church now living on 'the margin of society' seems to provide some sort of solace rather than effective animation.The difficulties have been exacerbated with the onslaught of the New Atheist movement. Despite defences offered by theologians and the like, the atheists' criticisms bring direct challenge to the meaning churches claim to hold and proclaim. This is not a new phenomenon. It has been growing since the enlightenment, gathered speed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and took flight with rapidly advancing science in the twentieth. Confrontation by the New Atheists is one founded on questions of contemporary evidence and meaning.Ironically the one Church that has landed itself in deeper strife than most and maintains conservative ground with a near breath taking defiance may be signalling a simple, direct hope for churches. Relic be damned! The election of Pope Francis has brought a fresh voice.The voice is remarkable not solely for profound theological discourse or defined judgements. Rather it is a voice appearing concerned for conversation among people, rather than categorisation of people. It is a voice that addresses Church as being a simple process concerned for focussed pastors and priests to step outside their establishments to reach needs in local communities. Francis seems concerned for the risky path of engendering conversations that build communities.Such thinking does not fit well into the applications of structured programmes. Nor does it provide static intellectual targets for empirically minded atheists. To employ a metaphor: it appears to be much more like gardening where one tills the soil, pulls a few weeds, nurtures new shoots with water and useful sustenance hoping enough is done for a reasonable crop. Gardening is a practical act of faith. It is a gift to the earth, to other people, to oneself.Incidentally gardening has long been a worthy, restful Sunday activity. It is one resonate with deep biblical imagery, similar to gathering with friends for food, conversation and re-creation where appearance matters little and presence means all.©John FairbrotherJanuary 2014

Follow us:

Follow us: