Writing

-

After a Wedding Feast

They have no wine

When the guests have departed,

the miracle has passed

and God has gone from his mother,

she scoops up the leftovers

to nurse in her lap,

knees spread apart, knows

again the humiliation, tastes

the last drops of wine

meant for a celebration

she helped enact.

Alone

with her need she watches

her secret load carried

like a golden seed

from her body

to lay in the fields

painted in purple.©Julie Thorpe

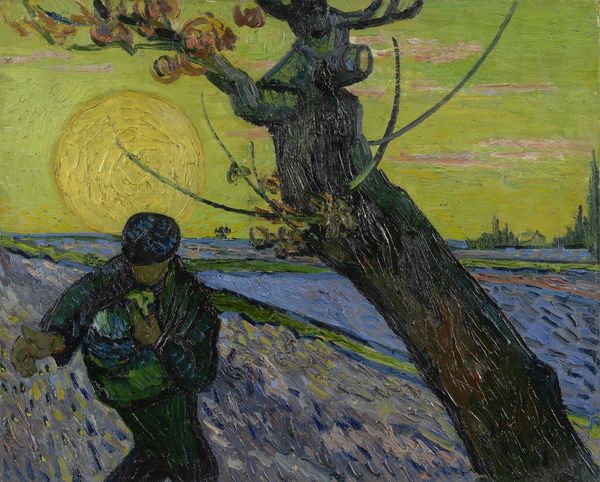

Image The Sower, Vincent van Gogh, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent Van Gogh Foundation) -

The Temple in His Bones

Reading from the Gospels

Lent 3, Year B: John 2: 13 – 22On my first afternoon in Rome a few years ago, I climbed on the back of my friend Eric’s motorcycle and set off with him to begin my acquaintance with the Eternal City. A few minutes down the road, he told me to close my eyes. When we came to a stop and I opened them, my field of vision was filled with one of the most impressive sights in a city of impressive sights: the Pantheon. Built in the second century AD, the Pantheon replaced the original Pantheon that Marcus Agrippa constructed fewer than three decades before the birth of Christ. A temple dedicated to “all the gods” (hence its name), the Pantheon became a church in the seventh century when Pope Boniface IV consecrated it as the Church of Santa Maria ad Martyres. It’s said that at the moment of the consecration, all the spirits inhabiting the former temple escaped through the oculus—the hole in the Pantheon’s remarkable dome that leaves it perpetually open to the heavens.

As churches go, it’s hard to top the Pantheon for its physical beauty and power. It was perhaps risky to see it on my first day, so high did it set the bar for the rest of my trip. Yet Rome, of course, brims with delights for the eyes, and the next two weeks offered plenty of stunning visual fare. Amid the calculated grandeur, I found that it was the details that charmed me: the intricate pattern of a Cosmatesque marble floor, the shimmer of light on a centuries-old mosaic, the inscribed marble fragments that had been unearthed and plastered to the walls. It was staggering to contemplate the countless hours and years that went into the construction of these spaces, or to fathom the vast wells of talent and skill that generations of architects, artisans, and laborers lavished upon them.

The Roman churches that most linger in my memory are those that possessed a clear congruence between the physical environment and its purpose—those places of worship that were not primarily tourist destinations but true sanctuaries. I felt this congruence keenly, for instance, in the Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere. The space intrigued me from my first moments in it, on the first evening of my trip. I would return several times, learning along the way that one of the many ways the church serves the surrounding Trastevere neighborhood is as a place of prayer for the Community of Sant’Egidio, a lay movement of people who work for reconciliation, peace, solidarity with the poor, and hospitality to pilgrims.

On the day that Jesus sweeps into the temple, it’s this kind of congruence that is pressing on his mind. We don’t know precisely what has him so riled up; after all, particularly with Passover drawing near, there are transactions that need to take place in the temple. As Jesus enters, he sees those who are attending to the business involved in the necessary ritual sacrifices, but he seems to feel it has become simply that: a business. Commercial transaction has overtaken divine interaction. Time for a clearing out, a return to congruence between form and function, to the integrity of the purpose for which the temple was created: to serve as a place of meeting between God and God’s people.

To those who challenge his turning over of the temple, Jesus makes a remarkable claim: that he himself is the temple. “Destroy this temple,” he says to them, “and in three days I will raise it up.” His claim stuns his listeners, who know that the sacred space in which they are standing—the Second Temple, which was in the midst of a massive renovation and expansion started by Herod the Great—has been under construction for forty-six years. John clues us in on the secret that the disciples will later recall: “He was speaking of the temple of his body.”

This scene underscores a particular concern that John carries throughout his gospel: to present Jesus as one who takes into himself, into his own body and being, the purpose of the temple. Richard B. Hays writes that in making the link between Jesus’ body and the temple, this passage provides “a key for much that follows” in John’s gospel. “Jesus now takes over the Temple’s function,” Hays observes, “as a place of mediation between God and human beings.” Hays goes on to point out how Jesus’ sometimes enigmatic sayings about himself in John’s gospel—for instance, “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me, and let the one who believes in me drink” and “I am the light of the world”—are references to religious festivals whose symbolism Jesus takes into himself.

Perhaps, then, it all comes down to architecture. The decades of work that have gone into the physical place of worship, the skill of the artisans, the labors of the workers; the role of the temple as a locus of sacrifice, of celebration, of identity as a community; the power and beauty of the holy place: Jesus says, I am this. Jesus carries the temple in his bones. Within the space of his own body that will die, that will rise, that he will offer to us, a living liturgy unfolds.

We will yet see the ways that Jesus uses his body to evoke and provoke, how he will offer his body with all its significations and possibilities as a habitation, a place of meeting, a site of worship. Calling his disciples, at the Last Supper, to abide in him; opening his body on the cross; re-forming his flesh in the resurrection; offering his wounds to Thomas like a portal, a passageway: Jesus presents a body that is radically physical yet also wildly multivalent in its meanings.

The wonder and the mystery of this gospel lection, and of Jesus’ life, lie not only in how he gives his body as a sacred space but also in how he calls us to be his body in this world. Christ’s deep desire, so evident on that day in the temple, is that we pursue the congruence he embodied in himself: that as his body, as his living temple in the world, we take on the forms that will most clearly welcome and mediate his presence. In our bodies, in our lives, in our communities; by our hospitality, by our witness, by our life of prayer: Christ calls us to be a place of meeting between God and God’s people, a living sanctuary for the healing of the world.

The season of Lent beckons us to consider, are there things we need to clear out in order to have the congruence to which Christ invites us? Who helps you recognize what you need to let go of in order to be more present to the God who seeks a sanctuary in you? How is it with your body—your own flesh in which Christ dwells, and the community with which you seek to be the body of Christ in the world? What kind of community do you long for—do you have that? What would it take to find or create it?

In these Lenten days, may we be a place of hospitality to all that is holy. Blessings.

©Jan Richardson

©Image The Temple in His Bones, Jan Richardson[Richard B. Hays quote from his chapter “The canonical matrix of the gospels” in The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels, ed. Stephen C. Barton.]

-

Passion

The spider webs glisten in the soft slanting light of a gilded Autumn in Aotearoa. The long white cloud has given way, for the moment, to golden luminosity. The intricate patterns and variations of the singing bellbird/korimako in the tree accompany my writing. In whatever way the song functions for this bird, unique to New Zealand, it is beautiful and compelling for me. I cannot imagine a world without birds. Such thoughts add poignancy to this season, soon to be farewelled. Storm clouds gather.It was Captain Cook who, in 1770, named the northernmost point of New Zealand's South Island, Cape Farewell, because it was the last land he sighted after leaving these shores for Australia at the end of his first voyage. The longest natural sandbar in the world, called Farewell Spit, is near the Cape. Whale strandings are common there. No-one really knows why. Volunteers from the aptly named Project Jonah know all about saying farewell.Jonah was regarded as a prophet in Islam, Judaism and Christianity. Inspired by his strange story of rescue and deliverance, those who work for Project Jonah care deeply about the welfare of whales and other sea mammals, their suffering and their needs. 'We believe that both animals and people matter,' they say. 'Whilst the animals are central to what we do, it's people that make our work possible'.In the Northern Hemisphere, there is another Cape Farewell, which juts out into the northern Atlantic Ocean at the southernmost tip of Greenland. It is the windiest region on Earth. Early Icelandic sagas describe the wild capricious winds at Cape Farewell blowing early Viking explorers from Iceland and Greenland off course to reach landfall in Canada and North America.Artist, David Buckland began The Cape Farewell project in 2001 as a cultural response to climate change. Moving beyond purely scientific debate to creative insight and vision, the project brings together artists, scientists, communicators from around the world...'The Arctic is an extraordinary place to visit...to be inspired...which urges us to face up to what it is we stand to lose', he says.The Paschal Mystery will soon occupy the thoughts of the Church and its people. Joyous song will give way to a walk with Jesus along the Via Dolorosa, the Way of the Cross, in Jerusalem. Over the centuries, millions of pilgrims have walked in His footsteps, beginning in the Muslim Quarter of that Abrahamic city along a winding path to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in the Christian Quarter.We do not have to go to Jerusalem. People of faith, in the week we call Holy will, in their own places of devotion, accompany Jesus and meditate and pray about the events of His Passion and His dying on Good Friday.His disciples, family and friends faced the end of the incarnation, the end of Jesus' presence on earth. Yet His farewell words to them tell a different story - of love, comfort, change, hope. The poet-prophet from Nazareth encourages them, as he does us, to imagine the promise of the resurrection, of what is to come.Although our spiritual awareness may wax and wane, the love of the Divine gifts us all we need to fare well in the journey of life. It is a Love that inspires us to be appreciative and generate abundance, wholeness and the sustaining of life in all of creation.And the whales and the birds and the wind sing a holy song.©Hilary Oxford SmithApril 2014Notes and References:Korimako is the Maaori name for the BellbirdImage: Passion, www.lifedesignsbycathleen.com -

Moments: A Blessing for the Wilderness

Jesus goes into the wilderness. There is something he needs there, a way that yet must be prepared within him.

Here at the outset of Lent, what can you see of the landscape that lies ahead of you? Might there be another place you need to go, physically or in your soul, before you are ready to enter the landscape that calls you?

Is there a space—a season, a terrain, a ritual—of preparation that you need; a place where you can find clarity, and perhaps a ministering angel or two? What might this look like?

Wilderness Blessing

Let us say

this blessing began

whole and complete

upon the page.And then let us say

that one word loosed itself

and another followed it

in turn.Let us say

this blessing started

to shed all

it did not need,that line by line

it returned

to the ground

from which it came.Let us say

this blessing is not

leaving you,

is not abandoning you

to the wild

that lies ahead,but that it is loathe

to load you down

on this road where

you will need

to travel light.Let us say

perhaps this blessing

became the path

beneath your feet,

the desert

that stretched before you,

the clear sight

that finally came.Let us say

that when this blessing

at last came to its end,

all it left behind

was bread,

wine,

a fleeting flash

of wing.©Jan Richardson

Image Brandon Messner: Mount Lemmon, Arizona USA, unsplash.com -

Moments: Transfiguration

(For use in prayer or liturgy)

For that one moment, ‘in and out of time’,

On that one mountain where all moments meet,

The daily veil that covers the sublime

In darkling glass fell dazzled at his feet.

There were no angels full of eyes and wings

Just living glory full of truth and grace.

The Love that dances at the heart of things

Shone out upon us from a human face

And to that light the light in us leaped up,

We felt it quicken somewhere deep within,

A sudden blaze of long-extinguished hope

Trembled and tingled through the tender skin.

Nor can this blackened sky, this darkened scar

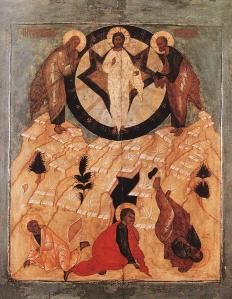

Eclipse that glimpse of how things really are.©Malcolm Guite

Image Russian-inspired icon of the Transfiguration, artist unknown -

Moments: The Well

(for use in prayer or liturgy)

Be thankful now for having arrived,

for the sense of

having drunk

from a well,

for remembering the long drought that preceded your arrival

and the years walking in a desert landscape of surfaces looking for a spring hidden from you for so long that even wanting to find it now had gone from your mind

until you only

remembered the hard pilgrimage that brought you here,

the thirst that caught in your throat; the taste of a world just-missed

and the dry throat that came from a love you remembered but had never fully wanted for yourself, until finally, after years making the long trek to get here it was as if your whole achievement had become nothing but thirst itself.

But the miracle had come simply from allowing yourself to know that you had found it,

that this time

someone walking out into the clear air from far inside you

had decided not to walk past it anymore;

the miracle had come at the roadside in the kneeling to drink

and the prayer you said,

and the tears you shed

and the memory

you held

and the realization

that in this silence

you no longer had to keep your eyes and ears averted from the

place that

could save you,

that you had been given

the strength to let go

of the thirsty dust laden

pilgrim-self

that brought you here,

walking with her

bent back, her bowed head and her careful explanations.

No, the miracle had already happened

when you stood up,

shook off the dust

and walked along the road from the well,

out of the desert toward the mountain,

as if already home again, as if you

deserved what you loved all along,

as if just remembering the taste of that clear cool spring could lift up your face

and set you free.©David Whyte

Image www.mindfulnessassociation.net -

Moments: Mysteries of the Mud

Reading from the Gospels, Lent 4, Year A: John 9: 1 – 41

“He put mud on my eyes.

Then I washed, and now I see.”

—John 9.15He could simply have touched him. Or spoken a single word. Instead, when Jesus encounters a man who has been blind since birth, he spits on the ground, turns the dirt to mud, and spreads the mud on the man’s eyes. Jesus tells him to go and wash in the pool of Siloam.

The man goes. Washes. And sees.

Appearing midway in our Lenten journey, this story reminds us that this season is a time for getting close to the things of the earth. Ash, wilderness, waters of birth, wellspring, mud: the images that have accompanied us these past few weeks impress upon us what an elemental fellow Jesus is. Throughout his ministry we see him touching the world around him, turning to the things of earth to help us see the things of heaven.

This week’s gospel reading underscores it for us: Jesus is no sterile savior. He is not interested in remaining tidy and removed. With a beautiful and earthy economy of gestures, Jesus reveals himself as one who is willing to fully inhabit the messiness of our world and of our lives. He is ready to enter into the muck with us. He engages the muck as a place where holiness happens: where sludge becomes sacramental, and through grimy eyes we begin to behold the face of Love, beholding us right back.

How might the mucky places, the thick places, the earthy places become the very places that Christ uses to help you see more clearly? Are there places or practices that contain something of Siloam for you—spaces where you can wash away what would hinder you from seeing, and allow your vision to become clear? How might you take yourself to your Siloam in this season, this day, this moment?

Blessing of Mud

Lest we think

the blessing

is not

in the dirt.Lest we think

the blessing

is not

in the earth

beneath our feet.Lest we think

the blessing

is not

in the dust,like the dust

that God scooped up

at the beginning

and formed

with God’s

two hands

and breathed into

with God’s own

breath.Lest we think

the blessing

is not

in the spit.Lest we think

the blessing

is not

in the mud.Lest we think

the blessing

is not

in the mire,

the grime,

the muck.Lest we think

God cannot reach

deep into the things

of earth,

cannot bring forth

the blessing

that shimmers

within the sludge,

cannot anoint us

with a tender

and grimy grace.—Jan Richardson

from Circle of Grace: A Book of Blessings for the Seasons

Image Mysteries of the Mud © Jan Richardson. janrichardson.com -

Moments: The Great Silence

In the great silence

the flowers seeded and grew,

the rain fell, the land took a breath,

exhaled.

The sun turned on its wheel

heedless to the forecast doom.In the great silence

the leaves folded, took their queue

and detached from the branch,

to become the first fruit

of a fallen carpet

destined for mulch.In the great silence, north and south,

the seasons changed,

exchanged batons.

The earth, on its axis, followed a path

long trodden,

defined by millennia past.And in the great silence

the people burrowed in,

appeared on occasion for air,

and breathed secure for knowing the earth

carried on its resolve,

resolute in purpose.And in the great silence

the planet rested,

the people rethought their focus

and slowed,

unfolded from the weight of lament and fear,

and returned as a world newly formed.And in the great silence,

the people rebuilt their altars,

with the memory of the lost

freshly engraved,

and with the lessons of the earth

and their treasures preservedthe people conceived of a new way.

©Ana Lisa de Jong

Living Tree Poetry

March 2020Image www.unsplash.com

-

Moments: Pilate's role...

Gospel: Matthew 26: 14 – 27: 66

I don’t know about you, but I think I have washed my hands more in the last few weeks than I ever have before! Especially before the strict lockdown came in and I was out and about in town and with people. The message to do this washing of hands as a way to counter Covid 19 has certainly got through. And there are some funny video clips around where people have re-written parts of well known songs to incorporate this idea of washing. For instance, Neil Diamond’s ‘Sweet Caroline’:

‘Hands – washing hands

Reaching out – Don’t touch me, I won’t touch you’And also a funny video clip from that great television series MASH. So things to make us smile in amongst all the difficulty of this time.

Washing hands. Well, in our gospel passage today (a long one I know) we come across someone washing their hands. Pilate. Trying to ‘wash his hands’ of his actions.

In my daily bible study notes with this passage, the author writes: ‘Plunge yourself into the story of Jesus’ passion and crucifixion, and find where you are in the story’. Well, I am choosing to concentrate on Pilate, with this ‘washing hands’ connection, and also because I lived with Pilate for several months, back in the early 1980’s! Let me explain.

My late husband Mark was a great singer and musician. When I first met him he was lead guitarist and singer in a band. After we married and moved to Dunedin he had his voice trained and sang in the competitions, winning the Dunedin Aria competition one year. He was also involved in Repertory and Operatic productions and he played the role of Pontius Pilate in ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’. He practiced at home, for months, and so I ended up knowing his role inside out and backwards. I still know the words of the songs Pilate sang in that show.

And so on this Palm/Passion Sunday, I want us to spend time looking at Pilate’s part in this unfolding drama. This man who washed his hands in the hope that it would absolve him of his actions….He has gone down in history as the judge of Jesus's trial, and in turn he has been judged for that. Many regard him as weak, a coward, a man who crumbled under pressure. Think for a moment of how you regard Pilate.

Now, let’s just look at what has led up to the point of encounter between Pilate and Jesus. If you read the full passage (and I would encourage you to do so) we see that there was a plot against Jesus as many regarded him as a threat to the establishment of the time. Judas agrees to betray Jesus. The disciples eat the Passover meal with Jesus and in that he talks of one who will betray him, one who will deny him. The disciples are aghast at that. This story is very familiar to us. We can feel the tension building. The drama beginning to unfold. Jesus prays in Gethsemane, alone. An incredibly hard time for him. He is arrested. Taken before the Jewish Council. Accused of blasphemy. Peter denies knowing Jesus and is heartbroken when he realizes what he has done. And Judas is heartbroken when he realizes what he has done. The story we know so well is quickly unfolding, and we can’t stop it! And now Jesus is taken to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor under the emperor Tiberius.

Matthew’s account of Jesus’ appearance before Pilate and his execution follows Mark closely, but with significant variations. As in Mark the trial before Pilate begins with the leading question: ‘Are you the king of the Jews?’ It could be easy for us to miss the gravity of this encounter: the major power of Rome, through Pilate its representative, confronts suggestions of an alternative power. Rome is a big deal. The power imbalance is enormous.

And let’s remember for a while an earlier time when this term ‘King of the Jews’ was used. In the Christmas story the wise men went looking for ‘the child who has been born king of the Jews’. Herod got to hear about that and in his fear of a rival power, ordered the slaughter of all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old and under. These were tough times when any sort of perceived rivalry for power would not be tolerated by the Romans.

So, Jesus had caused a stir at his birth, and we see it again in our passage today, as he stands before Pilate. There were no human rights conventions then. An individual coming up against the power of the state was very vulnerable. Are you the King of the Jews? Ponder that for a moment….

As the words of the song from ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ go:

Pilate:

Who is this broken man cluttering up my hallway?

Who is this unfortunate?

Soldier:

Someone Christ - King of the Jews

Pilate:

Oh so this is Jesus Christ, I am really quite surprised

You look so small - not a king at all

We all know that you are news - but are you king

King of the Jews?

Jesus:

That's what you say

Pilate:

What do you mean by that? That is not an answer

You're deep in trouble friend –

Someone Christ - King of the JewsJesus’ response to the question ‘Are you the King of the Jews’ can be seen as an ironic acceptance of the title. It also echoes his response to the High Priest who earlier asked him if he was the Messiah, the Son of God. There too he said ‘You have said so’. His responses, and then his silence, to both the High Priest and Pilate are infuriating and perplexing to them.

Matthew reworks the scene with Barabbas. It becomes Pilate’s initiative (not the crowd’s) to bring Barabbas into the equation. Choose Jesus Barabbas (Aramaic: son of the father) or Jesus (Son of God). The effect is to lay the blame squarely on the crowd. By inserting a report about the wife of Pilate and her dream, Matthew suggests that she, like Joseph and the magi of the birth stories, has a special connection with the divine. It could even indicate that he wants to exonerate Pilate. Washing his hands and declaring Jesus innocent might point in that direction. Matthew certainly points to the bloody consequences for Jerusalem and its inhabitants. The crowd say ‘Let the punishment for his death fall on us and our children!’ It is chilling.

So we get this sense that Matthew plays down Pilate’s responsibility in the drama, by introducing Pilate’s wife and her dream, by Pilate washing his hands, supposedly absolving him of any responsibility for Jesus’ death, by showing the crowd’s part in the story. But, standing back from the picture, we cannot overlook Pilate’s role. Whatever game he is playing in the narrative, he does not escape responsibility. The story cannot obscure the historical fact that Jesus was executed by a Roman official, on a Roman cross, as a political criminal. As one author puts it ‘There is no justification, historical or exegetical or theological, for reading the passion narrative as justification for anti-Judaism’.

Pilate knew that Jesus was not a criminal. He knew that the Jewish authorities were jealous of him. He had the crowd baying for blood, crying for Jesus to be crucified. He felt he was between a rock and a hard place so he had Jesus whipped and sent off to be crucified. He attempted to ‘wash his hands’ of it. I wonder how he lived with that decision.

In the show ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’, Pilate sings the following:

I dreamed I met a Galilean;

A most amazing man.

He had that look you very rarely find:

The haunting, hunted kind.

I asked him to say what had happened,

How it all began.

I asked again, he never said a word.

As if he hadn't heard.

And next, the room was full of wild and angry men.

They seemed to hate this man.

They fell on him, and then

Disappeared again.

Then I saw thousands of millions

Crying for this man.

And then I heard them mentioning my name,

And leaving me the blame.This passion narrative is a hard read. What strength Jesus showed. What depth of faith and determination he had. Even though we know that resurrection lies ahead, in this space there is betrayal, desertion, sadness, heart-brokenness, guilt, regret, desolation, confusion, anger, injustice, mockery, death. All the things that are part of our life’s journey at times.

On this Palm/Passion Sunday of the church year, there is the choice of celebrating the triumphant entry into Jerusalem (Matthew 21: 1-11) where the crowd spread their cloaks and branches on the road and people called out their praises to Jesus. A high point. And there is the choice of concentrating on the passion narrative, which we have done today. I usually do a bit of both as there is the danger that we can celebrate the triumphant entry into Jerusalem one Sunday, and the next Sunday celebrate the Resurrection, without having experienced the hard journey between. I always urge the congregation to attend either the Tenebrae service or the Good Friday service, in order to hear this story, to know the depths of it, and so better know the joy of the resurrection.

This year we cannot gather for such services, which is really hard. But we can read this passion narrative and reflect on it. And we can see how this narrative can resonate with different happenings in our own lives. Hard and tough times which seem so bleak we cannot imagine a better future. Yet God is not stopped by disaster. God is not stopped by human hatred or the powers that be. Even when evil seems to be winning, God is not absent. God is present in the midst of the disaster, sharing the pain, relieving the suffering, and reassuring us again and again that nothing is stronger than God’s love.

May we know the reality of that in our own living, and may we continue on this journey with Jesus – the one who brings us life in all of its fullness. Amen.

©Rose Luxford

Image Pilate Washing His Hands, Hendrik ter BrugghenThe Rev. Rose Luxford is Minister of St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church, Oamaru, Aotearoa New Zealand

Follow us:

Follow us: